Digital therapeutics (DTx) in primary care

The debate over DTx product definitions has been ongoing since their arrival on the market less than a decade ago. In brief, DTx products use algorithms instead of molecules to deliver clinically-validated therapeutic effects. Robust evidence and regulation are the main ingredients. What makes this conversation even more interesting is that many roads can lead to the same ambiguous destination. Bluestar by Welldoc was the first mobile prescription therapy via the 510(k) pathway for diabetes management for adults. Pear Therapeutics introduced reSET for substance use disorder via a newly created De Novo pathway after requesting the FDA to regulate them. Nightware, developed to treat nightmares, made its debut via Breakthrough Device designation, a program that can help companies get through either the 510(k) or the De Novo pathway quicker or with more guidance from the FDA (h/t Brian Dolan for helping me understand this nuance). Generally, the timeline for the 510(k) can be a couple of months while the De Novo pathway can take up to one and a half years (Figure 6).

In a recent editorial, Chief Clinical Innovation Officer at CVS Caremark calls for more consensus and less obscurity in identifying true DTx products and more consistent regulatory oversight. Organizations like Digital Therapeutic Alliance founded in 2017 are rising to the challenge to help all stakeholders navigate the DTx ecosystem. The 2021 IQVIA report further differentiates DTx and digital care (DC) products based on breadth of clinical indication (page 14). The following algorithm (somewhat) demystifies the identity crisis for digital interventions.

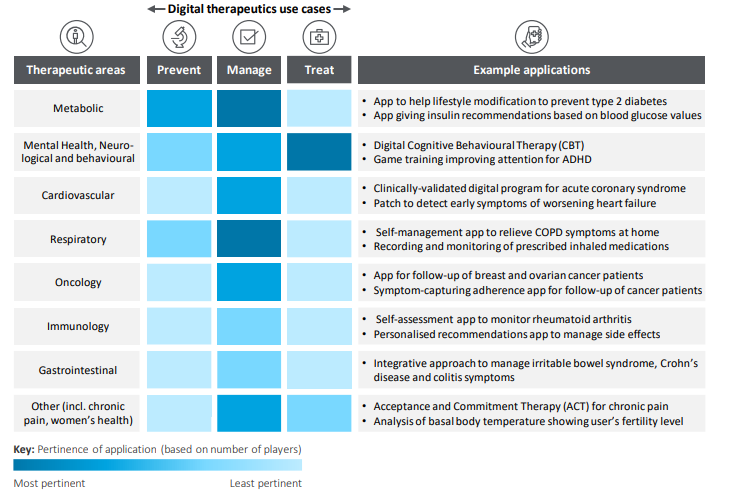

So what do the DTx products actually do? The 2021 Deloitte report has a nice illustration of use cases across prevention, management, and treatment spectra of DTx.

Segmenting the DTx market can be even less clear and full of outliers that represent the growing pains of providing medical care in novel ways. I found Blue Matter’s