Is virtualist a realist?

Why I changed my perspective on virtual primary care

“Why go through all of the medical training to become a virtualist? Serious question.” The sunk cost fallacy of the physical exam was palpable in my tone. Reading Jay Parkinson’s work, especially his take on asynchronous care, changed my perspective on virtual care. Here’s why:

Most of what happens in primary care does not demand an in-person visit (e.g. chronic disease management, preventive screenings, mental health counseling). The continuity of patient care, one of the main draws to practice primary care, comes through management of these clinical “projects.” We’re stuck with an assembly line of linear care in a nonlinear world that requires dynamic solutions.

Atypical presentations of routine complaints or acute presentation of less common illnesses get either overtreated à la defensive medicine or referred out not due to inability to “dig deeper” but because of time constraints. Patients receive suboptimal care and physicians feel frustrated.

Access to asynchronous communication enables the care team to tailor treatment according to illness progression. Digital care transforms the ever-fleeting time variable into an asset that strengthens rapport and builds trust.

Virtual-first approach to care is especially beneficial when exploring an unknown diagnosis and can then be paired with in-person visits for confirmation. Even medical education is adapting to teach patient-assisted virtual physical exams with emphasis on “webside” manner.

For virtual primary care to thrive, financial incentives in healthcare need to catch up with communication and project management technology (aka much of what we do in medicine). It’s no surprise DPC physicians are leading the charge in offering asynchronous care to their primary care patients. They actually have the freedom and flexibility to deliver the kind of primary care they signed up to do.

What about the tangible elements of in-person visits (i.e. the human touch) that deliver intangible benefits and transform skilled technicians into healers? Some like to hang on to the rituals. I wonder if this sentiment will only live on as long as the generations that teach it. The rhetoric of virtual health tech companies emphasize the high-touch longitudinal experience without ever laying hands on patients. Are they the misunderstood geniuses who get the real needs of patients/consumers or simply savvy entrepreneurs that can move patients across the billing system more efficiently?

Health tech is on a mission to “unbundle” medicine so we can end up with a VC-backed “solution” for each ICD-10 code. Is this a good thing? Perhaps if you have Z73.2. The harder question is how can virtual care extend the value of primary care without fragmenting its comprehensiveness?

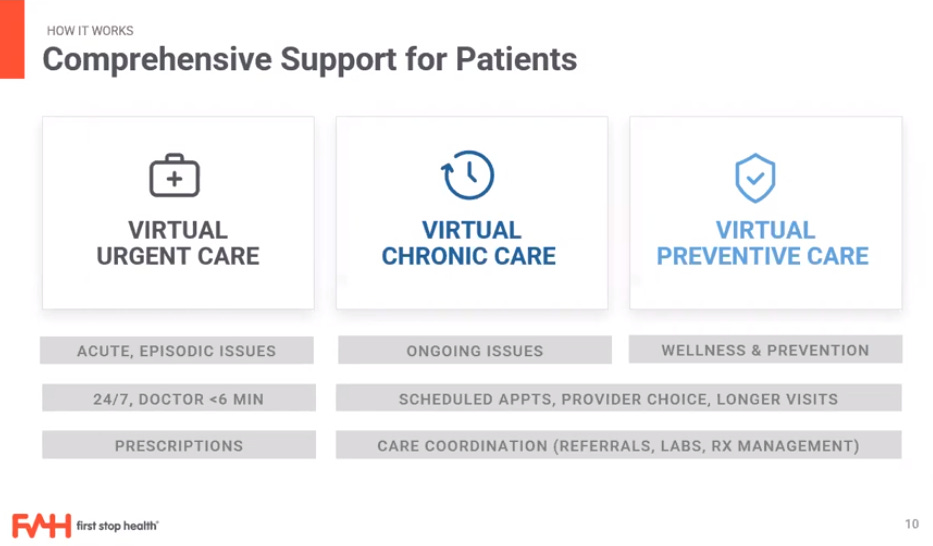

Companies like First Stop Health ($13M) focus on B2B solutions for self-insured employers through a menu of primary care options: urgent, chronic, and preventive.

Crossover Health ($281M) initially focused on corporate and hip companies like Apple and Facebook that generally have younger and healthier employees via their "Commercial Advantage” approach. Now they are extending services D2C for $200 per month. As an aside, majority of the individual DPC doctors often charge half this price. There even exist outliers like Dr. Lassey in Kansas who charges $10 per month for pediatric primary care. Are they undercharging because they want to make good primary care affordable to the masses or because they are bad business people? Many are just happy to have a way of practicing medicine on their own terms as opposed to working FFS (aka working for BUCAHs).

An entire cottage industry is emerging to supply virtualists to handle the influx of patients: Open Loop Health ($11M), SteadyMD ($35M), Wheel ($216M) et al. The word on the street is that working in clinical capacity for companies like Teladoc (TDOC:NYSE) and Amwell (AMWL:NYSE) is lackluster. It’s episodic care that too can lead to suboptimal care or increased referrals to urgent care simply because of limitations of virtual evaluation without confirmatory exams, labs, and imaging. However, for some clinicians convenience of working on their own schedule outweighs the daily grind of traditional healthcare. Practices who partner with services like Get Labs ($23M) and Sprinter Health ($37.6M) to outsource the labor intensive components of clinical encounters naturally extend the value of virtual primary care. Rezilient Health ($4.7M) is positioning themselves for tactile internet to take virtual evaluations to the next level. In my opinion, bringing back comprehensiveness to primary care is the winning solution for patients, those caring for them, and those paying for that care.

For the entrepreneurs out there, the AMA has put out a playbook on how to do telemedicine like a pro. Interestingly, telemedicine fellowships are popping up. Telehealth Leadership Fellowship at Jefferson Health was designed and funded by Teladoc which recently rolled out a framework for integration of virtual care for employers.

A buffet of offerings exist for digital health services to grow-your-own virtual operation. Software has really changed what’s needed to run a clinic.

Trying to make sense of virtual primary care has opened my mind to a much bigger universe that combines health technology and medicine, each bottomless in its own way. I find the combination fascinating. This leads to me the real question I should have asked at the beginning, “What do we need to unlearn about primary care?”