The Evolving Primary Care Workforce

Most of us would agree that there is more dysfunction than “function” in our primary care system. I certainly don’t feel comfortable aging into the system we have today. The tea leaves (and data) show us that the primary care workforce is undergoing a major transition that is poised to disrupt the status quo. It’s unclear whether things will get better or worse, but they sure aren’t going to stay the same.

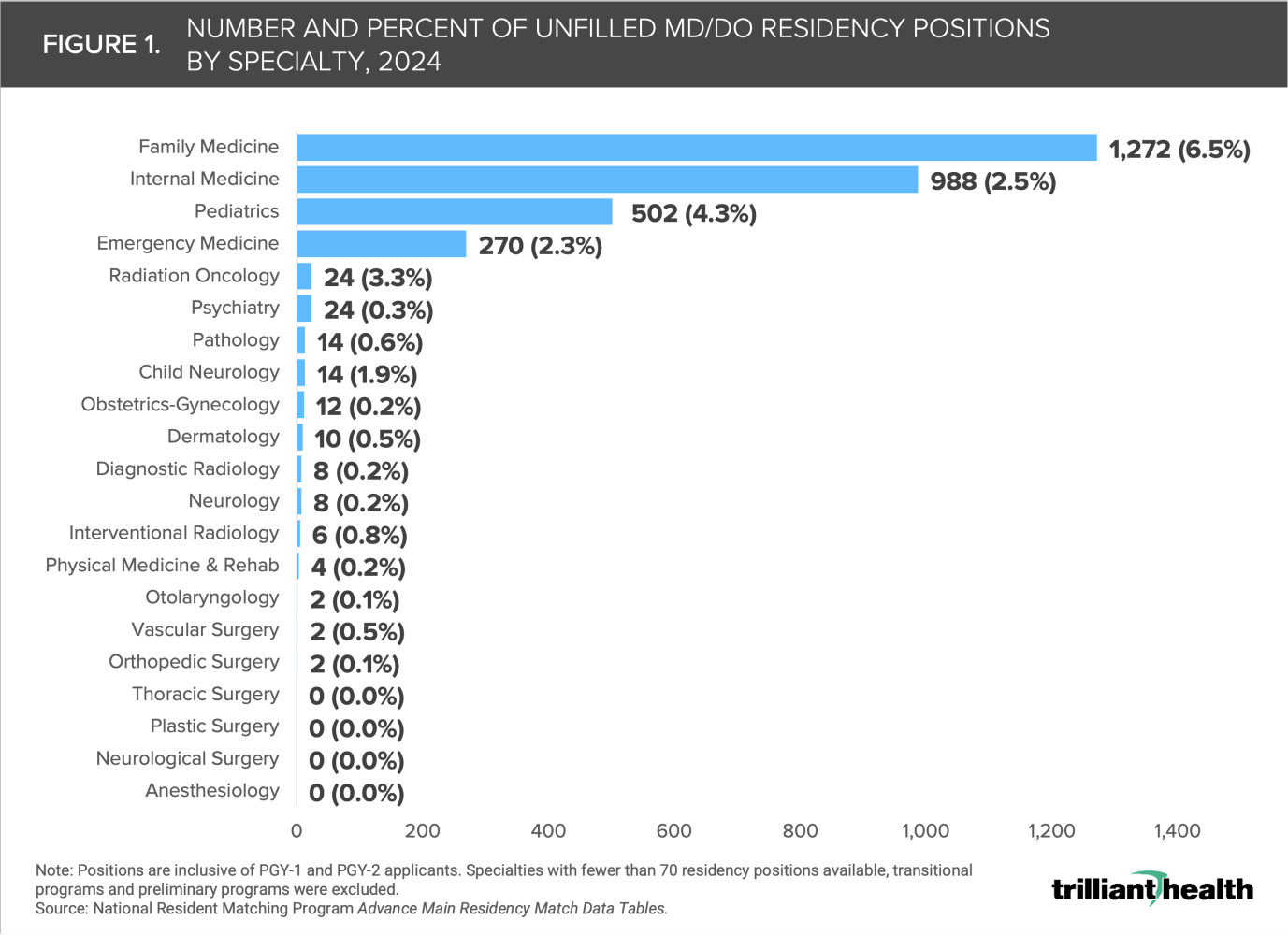

“You’re too smart to go into primary care” has been the hidden curriculum across medical schools during my training. My medical school mentees confess not much has changed recently. Nonetheless, some (albeit fewer and fewer) primary care diehards persist against odds and end up in family medicine, pediatrics, or internal medicine. Anecdotally though, many graduates “back into” primary care because they were not competitive enough for other specialties. The 2024 residency match rate data tells the real story of where this trend is heading (Figure 1). Additionally, many physicians who transition into primary care from fields like hospital medicine or emergency medicine often do so not out of an original desire to practice primary care, but rather as a response to burnout or dissatisfaction in their previous career trajectory.

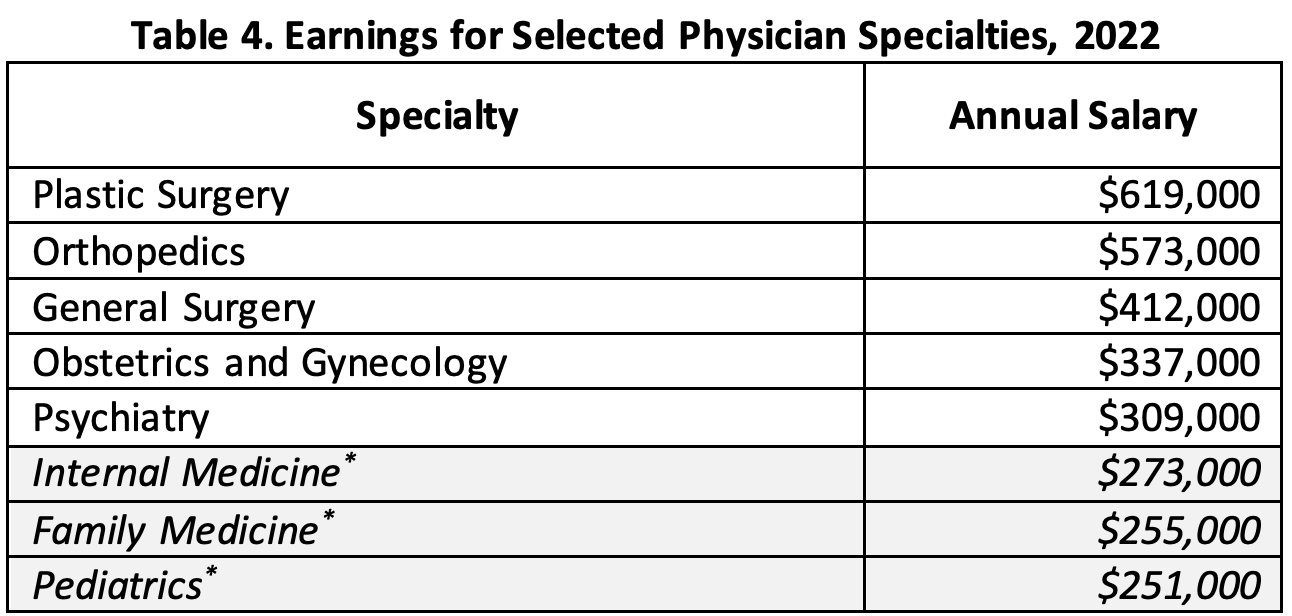

PCPs make significantly less compared to their colleagues (Figure 2). Medical schools have experimented with free tuition to potentially offset lower earning potential for those pursuing primary care specialties. Unfortunately, this has not proven to be true.

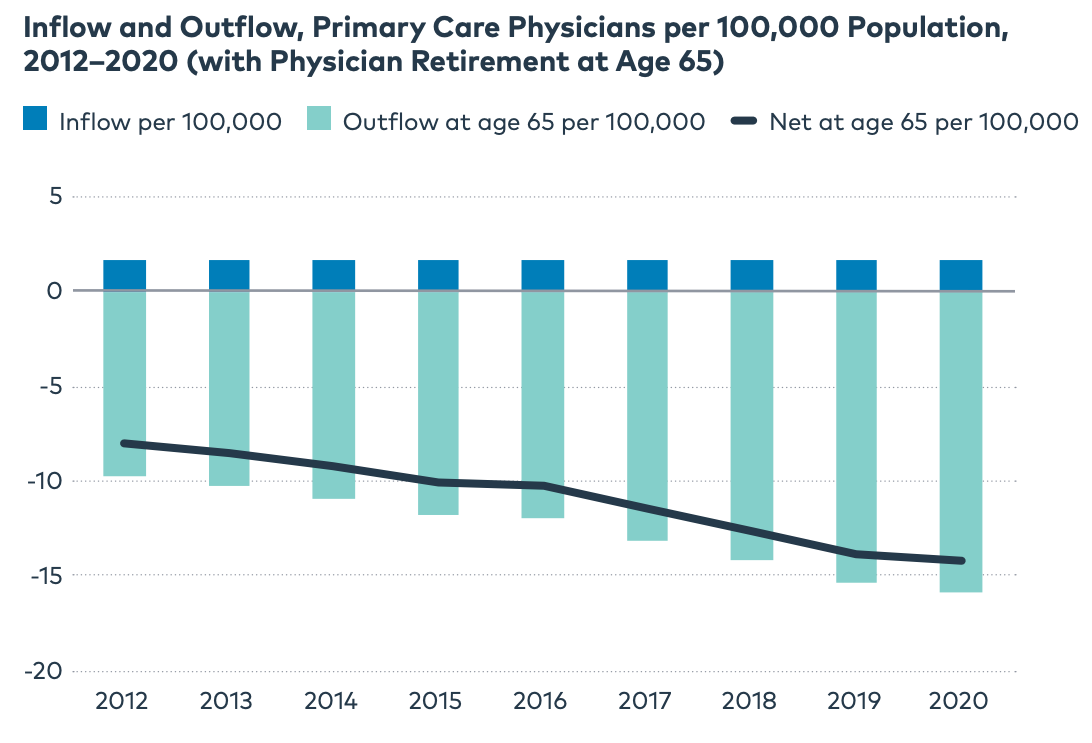

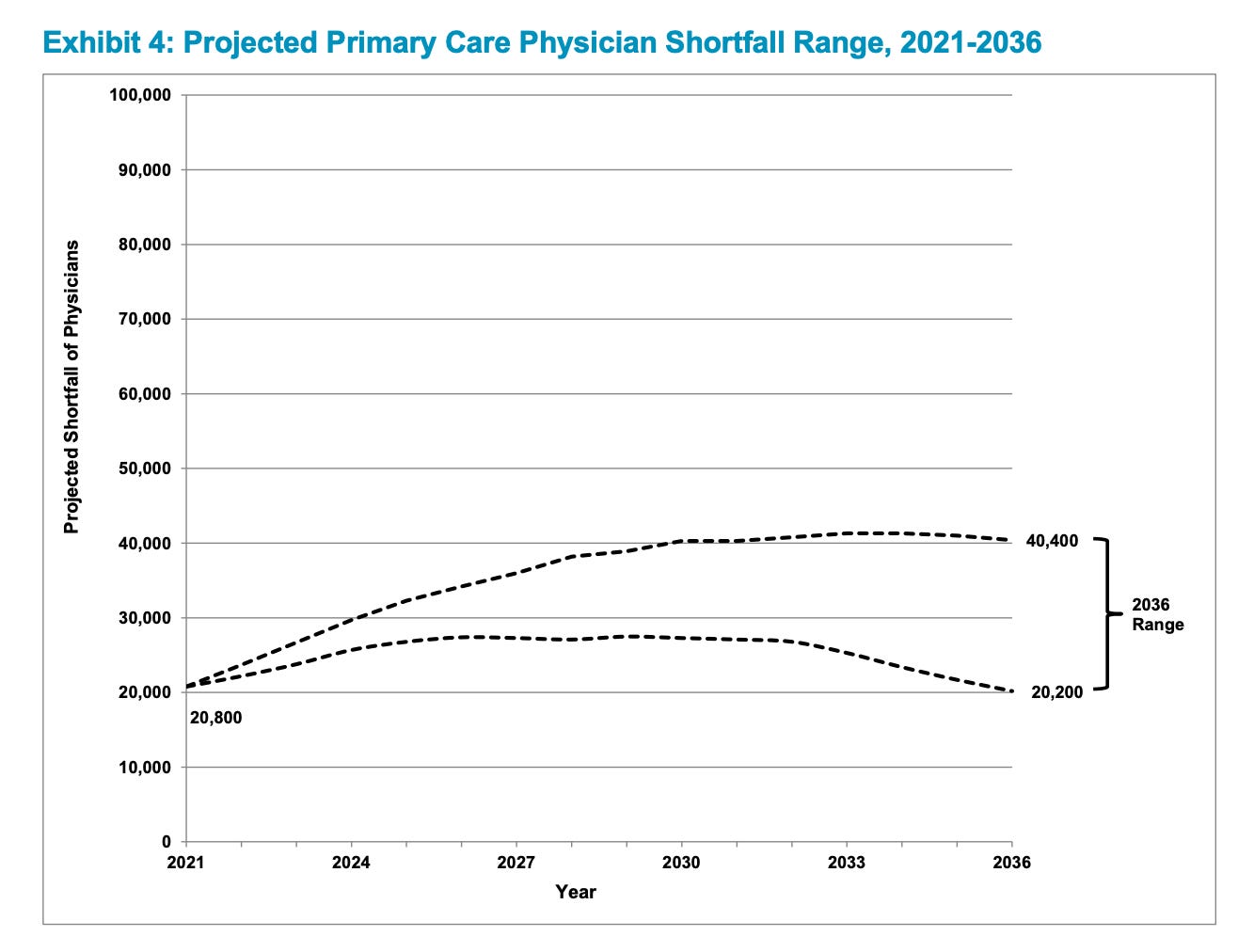

The Primary Care Collaborative illustrates the increasing outflow of PCPs in the last decade (Figure 3). Meanwhile, the AAMC predicts a shortage of up to 40 thousand primary care physicians over the next decade (Figure 4). The magnitude of this problem will be felt across half of the physician office visits in the US. Only a small and privileged sliver of the population can afford to ignore the problem of such epic proportions.

What’s the big deal? Primary care matters. Plenty of evidence shows high ROI on primary care. For example, Oregon’s Patient Centered Primary Care Home (PCPCH) program found that $1 dollar investment in primary care returns $13 dollars in savings. Another study found that every 10 additional primary care physicians per 100, 000 population was associated with a nearly 2 months increase in life expectancy.

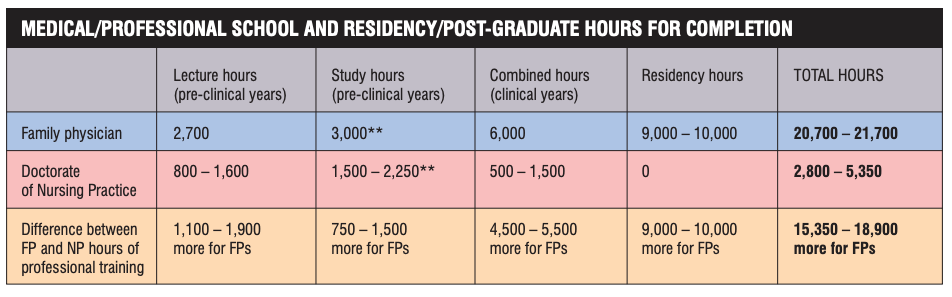

How are the market forces correcting for the declining primary care physician supply? The rise of advanced practice providers (APPs i.e. NPs and PAs) are absorbing the demand and filling workforce gaps. It’s a practical solution, especially for those in the business of healthcare. APPs are usually half the cost of physicians and are much quicker to “produce” (Figure 5).

To appreciate the context of the magnitude of the looming workforce challenges, it’s important to understand how vastly different physician and non-physician training actually is. Bringing up this distinction in training is not to label who’s “better” but to reinforce that clinical experience is at the heart of this discussion. I have learned a great deal of clinical pearls from those with more mileage than me, irrespective of their degree. I have also met physicians whom I would not recommend to my frenemies. Being good at medicine takes time. There are no shortcuts to high-quality care, even with AI copilots.

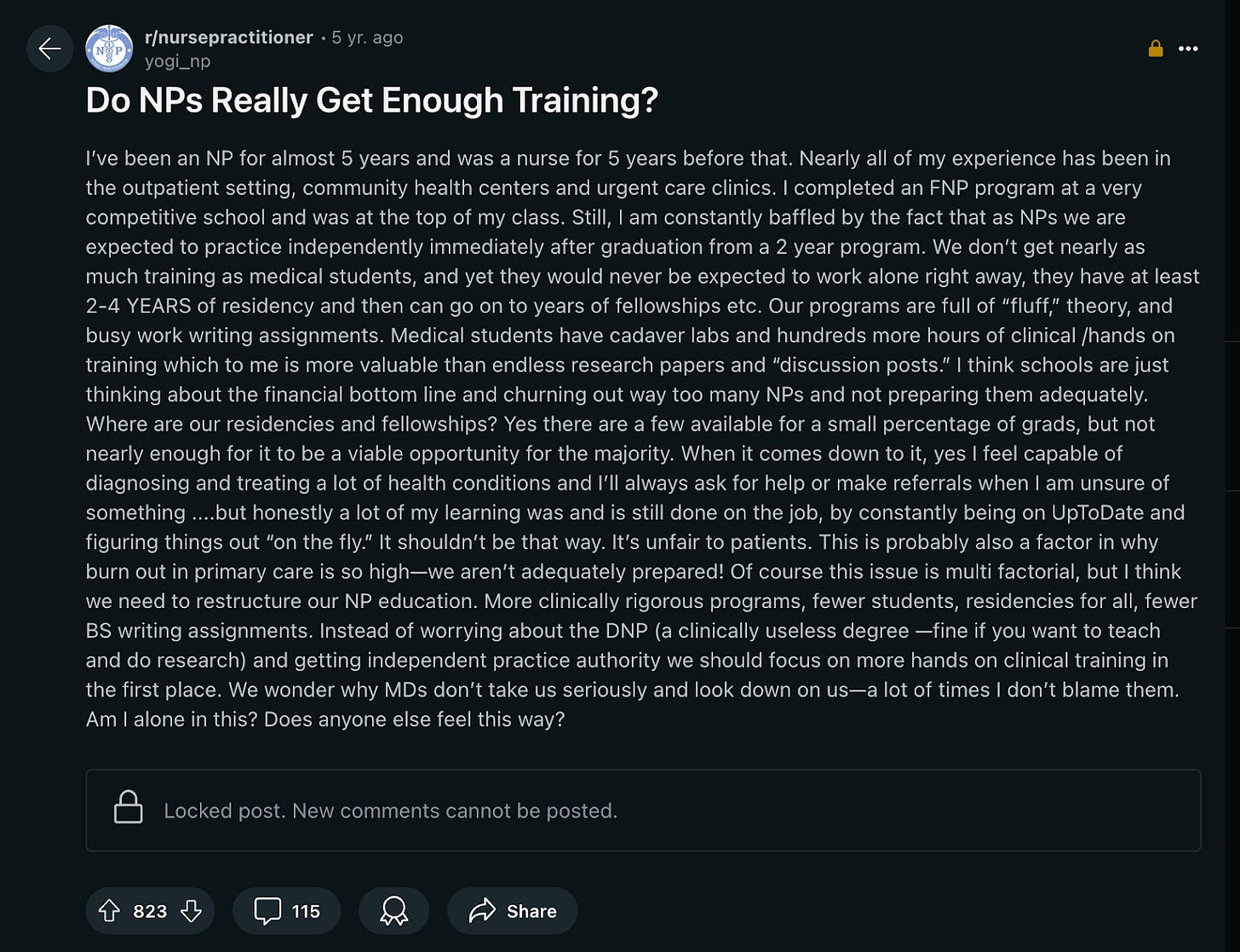

Based on candid conversations with newly minted APPs, many share a common sentiment of feeling woefully unprepared to handle the breadth of undifferentiated patients and the complexities of chronic illness exacerbations across urgent care and primary care settings. Their frustrations include being expected to do the same work as physicians, i.e. see the same number of patients in a day, treat the same type of cases irrespective of complexity, and perform the same type procedures. Many have come forth with critique of their own training (Figure 7). A recent article has shed more light about “predatory institutions” that contribute to this trend.

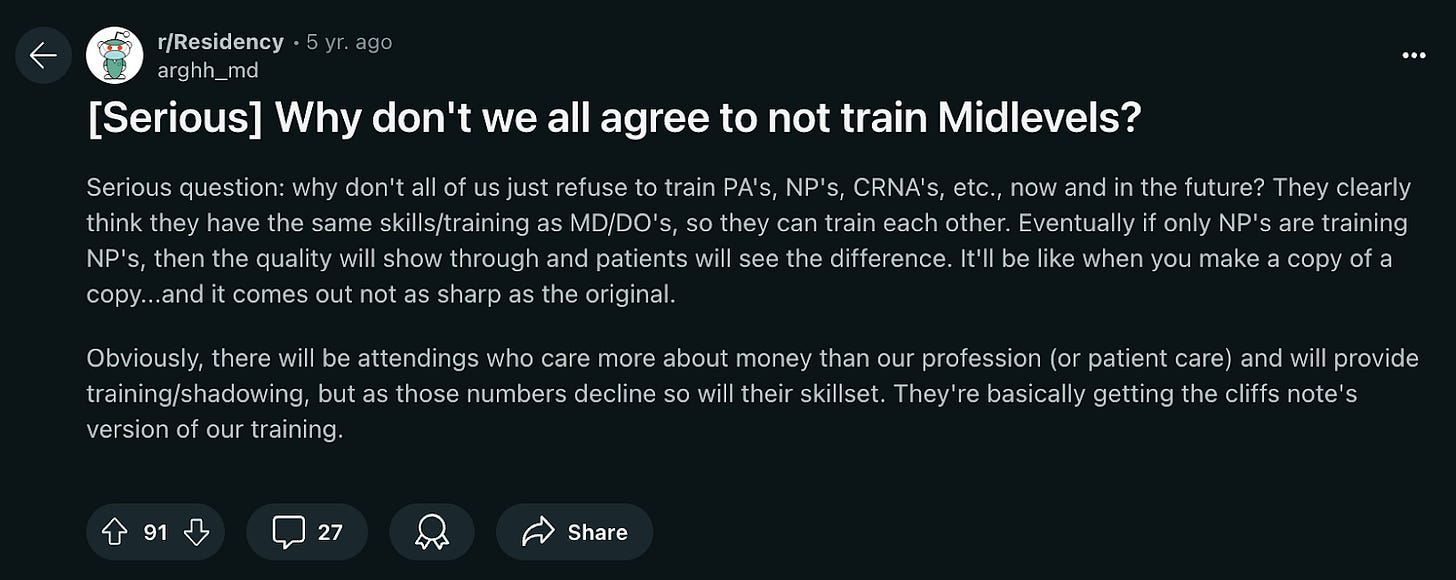

The parallel conversations in the physician community have been disheartening to witness (Figure 8). If we perpetuate such silos in healthcare, we’ll only further entrench the gaping disconnect among those delivering patient care.

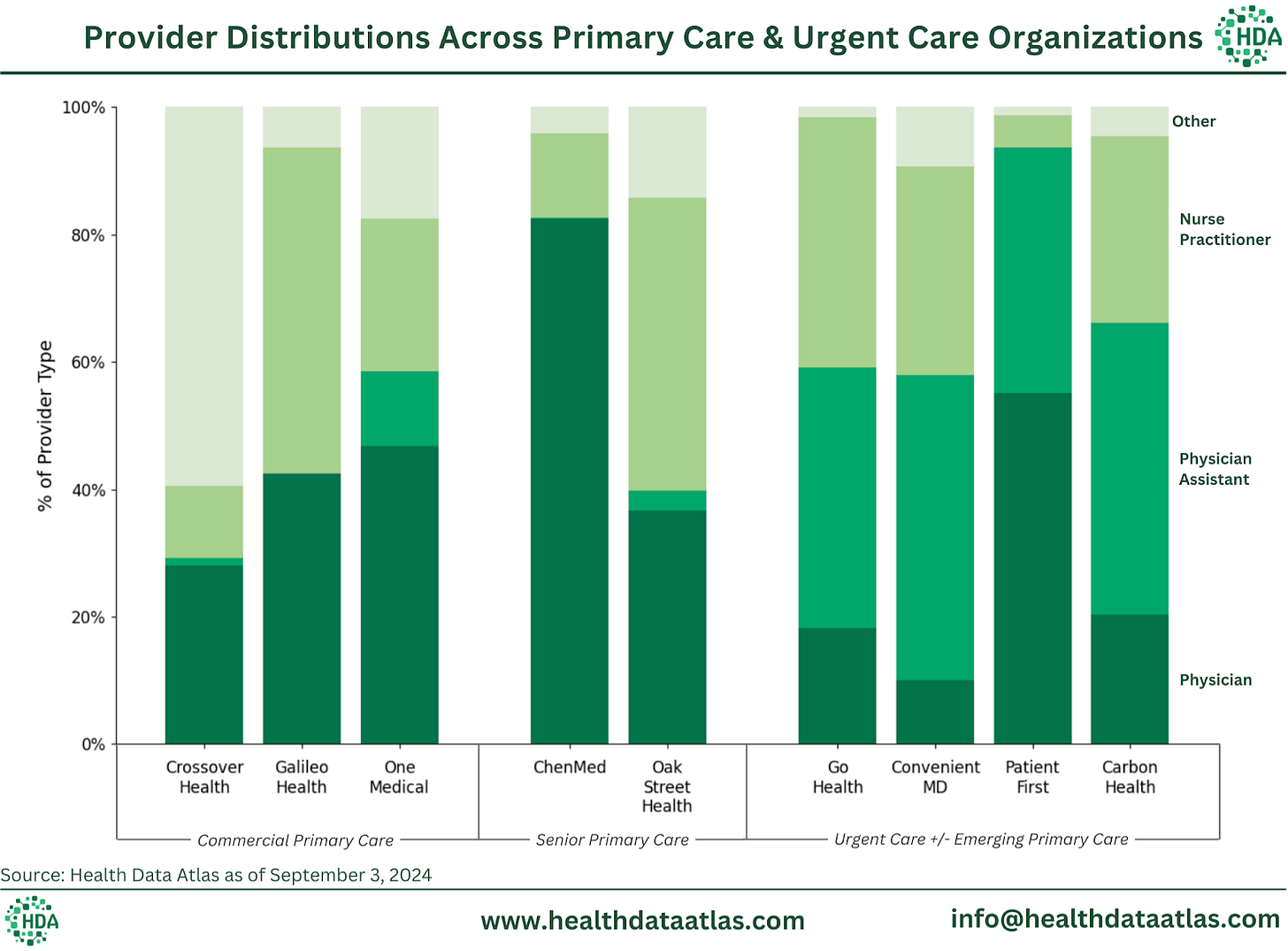

Let’s peel back the curtain on workforce composition at select large primary care and urgent care organizations based on billing NPIs (Figure 9). Not surprisingly, much of clinical care is delivered by non-physicians on aggregate. It’s worthwhile to note that ChenMed does not rely on NPs as much as others including its senior primary care counterpart Oak Street Health. Market trends indicate that urgent care centers must integrate primary care services to remain competitive. Patients now expect access to primary care at every healthcare “front door,” making it an essential service line rather than a unique selling point.

Note: Special shoutout to Michael Stratton and his team at Health Data Atlas for crunching the numbers and illustrating this data.

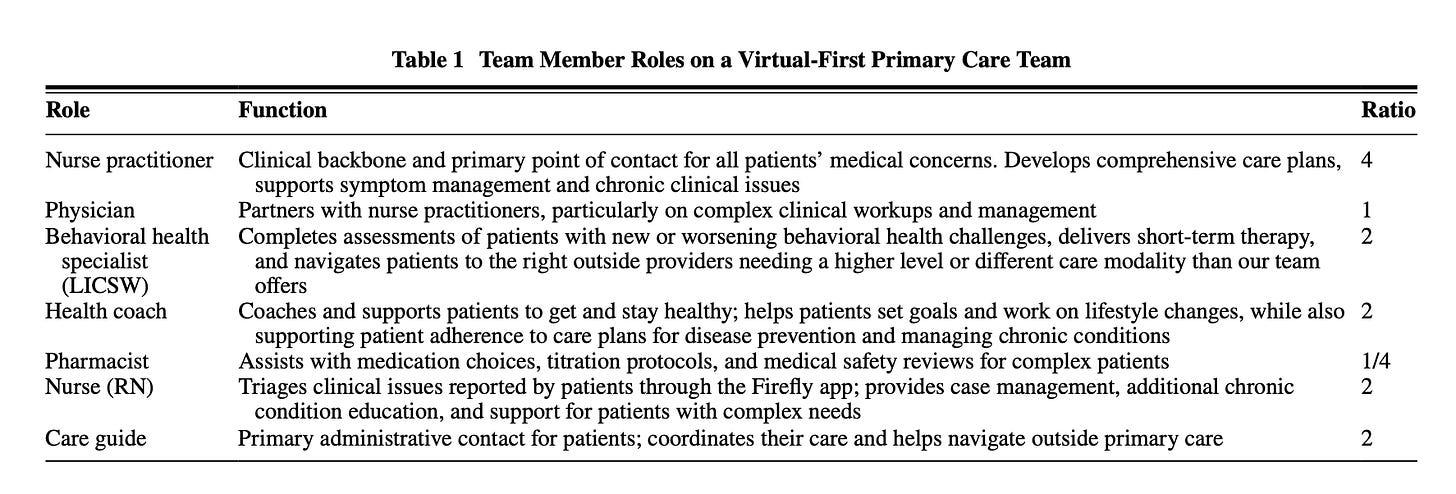

This provider distribution data reveals significant variability in workforce composition that is generally tackling similar “jobs to be done” across acute and chronic care settings. No single model has emerged as clearly superior. We're seeing a lot of experimentation. For instance, Firefly Health employs a virtual-first primary care model that relies on nurse practitioners as the clinical backbone of their interdisciplinary teams with physicians stepping in as partners on complex cases (Figure 10). This approach aims to match patients with the most appropriate provider for their specific health needs, potentially optimizing both care quality and resource utilization. However, we still don't know which approaches actually work better and what the ideal team composition should be.

Clay Christensen’s prediction has come to pass: “the host of technological enablers will fuel the disruption of specialists by primary care physicians in the future. In addition, these same technological advances will enable nurse practitioners and physician assistants to disrupt primary care physicians.” Unlocking effective collaboration between APPs and physicians is a key strategy for addressing the workforce challenges we are facing. This effort starts with reimagining medical education to make every clinician more effective and efficient. One approach is to integrate electronic medical records (EMRs) into the curriculum as a core educational tool, elevating clinical training to match the demands of the real world. XPC Clinic is leading by example. The future of primary care depends on our ability to innovate across education, technology, and care delivery models. By facilitating collaboration to enhance clinical training, we can build a primary care system that's not just functional, but truly thriving—one that we'd all feel comfortable aging into.

Thank you to Matthew Sakumoto and Michael Hobbs for reading drafts of this.

Brilliant. Interesting that many organizations, especially in Direct Primary Care, are advancing game-changing models of care that mostly involve physicians seeing fewer patients than ever! It is definitely the right of approach from an individual patient point of view, but is infinitely far from a practical solution given all the constraints you so eloquently organize in this article.

I am a primary care physician with my own practice. My wife is an APRN with me, and we just hired another APRN, who is very smart but fresh out of school. I have worked with several PAs and APRNs in the past. I agree with the article that freshly minted mid-levels are woefully unprepared to care for patients. When my wife was in APRN school at UConn, I looked at her curriculum, and it 1/3 was a complete waste of time. She barely got any clinical time at other practices. We were lucky that we had our own practice so I could train her (which is what I am doing now with our new APRN).

The other question about why MD/DOs don’t train midlevels. The colleges offering these programs are predators. They don’t want to pay MDs/DOs to train their students (I also train medical students and am compensated for my time by the University). They offer CEUs, which we cannot use, so they barter with other midlevels to train their students by offering CEUs. This creates another problem, as these midlevels get their CEUs from training and do not attend actual CEU programs where they can learn.

These programs have created a very strong lobby to convince legislators that they should be able to practice independently. The legislators give in because these lobbies are funded by large hospital systems that benefit tremendously from cheap labor.

By the way, I got a call from the Yale PA program several years ago to train their PAs. When I asked about compensation, I was told that being a doctor, it is my responsibility to the community to train the next generation of clinicians. When I told the administrator that I was happy to train their PAs if they would forgive their tuition, he said it was above his pay grade to make that decision. Needless to say, Yale never called me again.

Sudeep Bansal, MD, MS

Owner, Avanta Clinic LLC

Author/Podcaster at www.PCPLens.com