Why is primary care more important in Q4?

Understanding the seasonality of care gap closure

This article is a special collaboration with Alex Colavin, PhD who completed XPC Fellowship while building Threshold Health.

Care gaps represent the delta between what clinical guidelines recommend and what patients actually receive. They exist because patients miss preventive screenings (shoutout USPSTF), don’t fill prescriptions or struggle to manage chronic conditions. Most people know that taking care of our health early pays dividends later, but here are some facts to drive home the point:

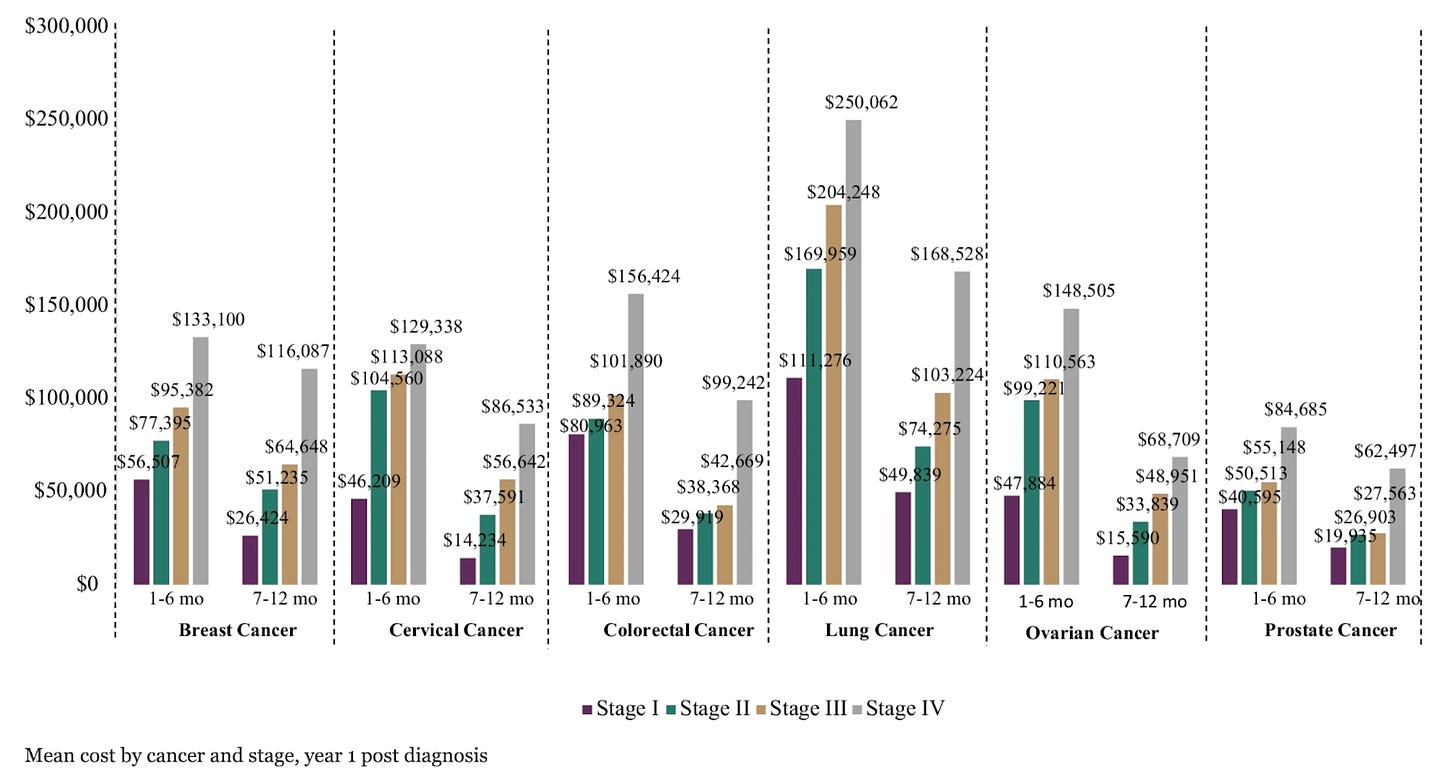

Treatments for later stage cancers are about $100,000 more expensive per year for every additional stage (Figure 1).

Patients who develop diabetes cost $13,000 more per year than patients with pre-diabetes.

Despite the clear benefits to patients and growth of value-based objectives for payers and providers, the uptake of preventive care is trending down. From 2015 to 2020, US adults who received all recommended preventive services dropped from 8.5% to 5.3%. While some specific measures have improved, historical data from NCQA shows most population-level quality metrics have changed little over the last decade.

Though individual patients face a huge diversity of obstacles to accessing care, there are also larger structural factors playing out nationally that make it challenging for healthcare organizations to effectively organize efforts to improve patient adherence to preventive care.

Besides patients, who else is reaping the benefits of closing these gaps?

For most of the last two decades, health plans were the primary beneficiaries of quality bonuses associated with increasing the proportion of patients who receive preventive care. Perhaps most prominently, Medicare Part C (aka Medicare Advantage) uses a 5-star system that directly measures the population-level access and adherence of preventive care services to grade health plans. A half-star change in a rating can mean $40M less in revenue for a health plan of typical size (~250,000 members). It’s evident that health plans are incentivized to care about care gaps with so much revenue at stake.

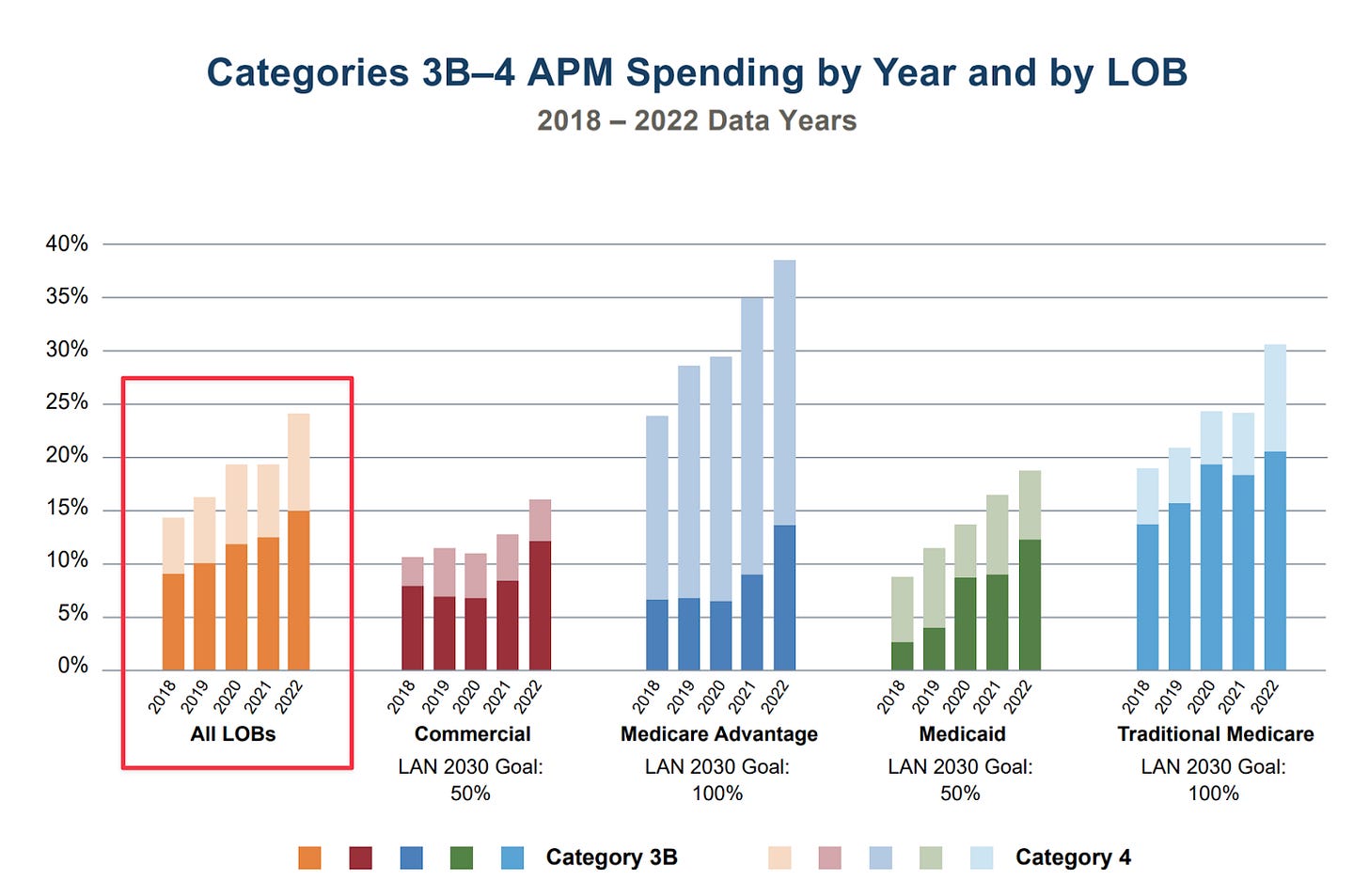

In the last few years, we have seen a rapid increase in the fraction of medical groups participating in contracts with health plans that share in quality incentives, reflecting the increasing popularity of value-based care (VBC). In 2023, $1 in $4 distributed by payers is associated with risk-sharing contracts, nearly doubling since 2018 (Figure 2).

In principle, primary care physicians are well positioned to engage patients and deliver preventive care, both because of their trusted relationship and knowledge of community resources. In practice, PCPs get caught in the tangled web of quality measures across the payers they contract with. For example, in a recent study of PCPs from one integrated health system, medical groups were keeping track of over 50 distinct quality measures across 10 different contracts with health plans. Even if there was more alignment across payers, primary care teams, and patients on which measures to prioritize, PCPs would require over 14 hours per day to provide recommended preventive care for all their patients. With an ever increasing number of screening guidelines, PCPs cannot reasonably tackle care gap closure alone.

Goodhart’s law warns us that dysfunction can arise from incentivizing improvement of measures that are imperfect representations of some true underlying objective. “Managing the measure instead of the patient” can incentivize the unintended behaviors.

For example, for quality measures intended to improve the control of blood pressure, only the last blood pressure reading of the year counts. This can incentivize organizations to prioritize blood pressure reduction campaigns at the end of the year. Similarly, medication adherence measures only consider whether a patient fills their prescription on time, not whether the medicine is actually being taken, leading to campaigns focused on at-home delivery of medication or encouraging extended day supplies.

Another common fear of care gap closure incentives is that contracts with different quality objectives will drive physicians to treat patients from one health plan differently from another. This concern is why it’s so important for medical groups to be thoughtful when designing incentive programs that encourage their physicians to close gaps. In fact, some practices have deliberately avoided care gap incentive programs for physicians for this reason.

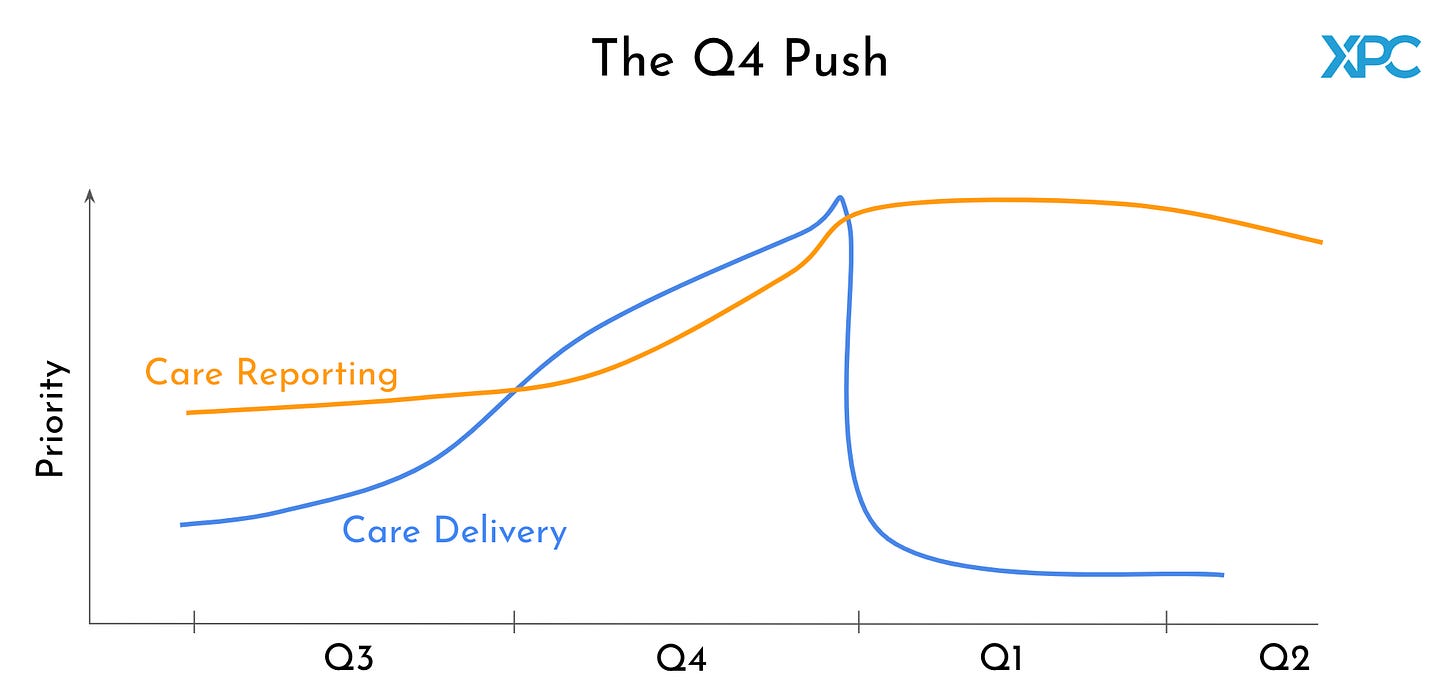

The frantic “Q4 Push”

While clinicians close care gaps with their patients all year, organizations only become aware of emerging population-level care gaps near the end of their annual VBC contracts. Only care gap closures that occur before the end of the contract year count towards that year’s quality measures. In contrast, organizations have several months after the start of the next year to document care delivery of gap closure from the previous year. The result is an unintended whiplash of changing priorities: deliver as much care gap closure as possible before December 31st, and then focus on challenging documentation in the new year.

This short, cyclic demand window for care gap closure undermines the intent of population-level quality measures and strains the limited resources of healthcare organizations, especially in the context of other year-end efforts (like HCC gap closure, CAHPS surveys, or re-enrollment). For example, staff tasked with calling patients and making appointments in Q4 get reassigned to tracking down and documenting proof of care delivery from the previous year.

As a result, an entire cottage industry has emerged of vendors who help healthcare organizations surface, close and document care gaps. In particular, the emphasis on reporting requirements from different health plans has led to the adoption of NLP and other advanced technologies to facilitate the Q4 push. Similarly, third party at-home visits, at-home tests, mammobuses and other services are in full swing in Q4 helping health plans rescue their at-risk care gaps.

Efforts to engage patients with important preventive care services during the Q4 push are often primitive and deeply frustrating for both the patient and the healthcare organizations. This is true for payers, clinicians and everyone in between.

Here are some horror stories from the trenches:

One payer spent hundreds of thousands of dollars staffing a new call center with 20 full-time temp workers for the last 12 weeks of the year simply to call every single one of their members with a care gap. They also proactively sent every patient behind on their colorectal screening a FIT kit.

Providers often have 10+ VBC contracts with dozens of care gaps. Every health plan is faxing them “chase lists” of their members with outstanding gaps. In one case, a health plan sent a provider group a large stack of prepaid Walmart gift cards with vague instructions to use them to get patients to come in for their annual wellness visit. Unfortunately, most of the gift cards ended up last in desk drawers instead of in the hands of patients.

Patients describe this time of year as one that erodes trust with their healthcare teams. Some patients receive several FIT kits and encouragement from their health plan – whom they are reticent to trust. Other patients will try to get preventive care only to find that there are no appointments available for months due to increased demand.

The result is a fragmented mess of stakeholder organizations stepping on each other's toes trying to close gaps. The emergence of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and Independent Physician Associations (IPAs) between payers and patients has further complicated care gap closure efforts.

With so many contracts and quality objectives, how do healthcare operators choose which gaps to go after?

Because there are not enough resources nor enough time to achieve perfect scores for all quality objectives across all plans, VBC organizations will go after some care gaps and ignore others. Here’s a preview of some prioritizations:

Health plan contracts will have obligatory quality minimums in addition to optional quality incentives. If a medical group is behind on contract obligations, especially for those representing a large portion of the patient population, then efforts to close those gaps will get prioritized.

Among optional gaps, medical groups will focus on those associated with the largest incentive bonus; these often come from the VBC contract that represents most of their lives under care.

Once a contract is prioritized, operators focus on the most achievable measure objectives, based on the ease of improving them and how close they are to their goal. This can unintentionally result in deprioritization of the metrics that need the most attention.

Not all gaps are equally easy to close. Some gaps, like measuring blood pressure, can be closed by a medical assistant over the phone. Other gaps require an office visit with a physician. Priority gap closures also change as appointment availability shrinks and time available in Q4 runs out.

While some large organizations, particularly academic medical centers, have developed effective care gap closure campaigns, the majority of small and medium-sized medical groups struggle with the infrastructure and resources needed to effectively pursue population health objectives. Several opportunities exist to quell the chaos of the Q4 push. For example, it may be necessary to revise the arbitrary reporting rules that govern care gap closures. Implementing a rolling measurement period for care gap closures could help smooth out the Q4 curve, allowing for more consistent, year-round efforts. Additionally, extending documentation periods or providing provisional credit for scheduled appointments could alleviate pressure on healthcare organizations, enabling them to distribute resources more efficiently throughout the year.

The challenges underlying pursuit of population-level goals are not unique to the Q4 push to close care gaps. Just as value-based contracts are proliferating with primary care clinics, an increasing number of digital health companies specialized in specific clinical areas enter risk-based contracts with payers. As the network of organizations sharing risk and pursuing population-level objectives is growing, the patient relationship is splintering between more and more healthcare operators vying for their attention. Technology that connects care across organizations will be key to achieving population health goals.

Thank you to Ajay Haryani, Ian Perlman, Alex Kazberouk, Joel Gray, and Doug Murad for reading drafts of this.

Thank you posting the problems related to quality measurement. I run my medical practice, have worked in value based care and currently in vbc contracts. I agree with the problems with data collection and insurance companies hold most of the cards when submitting supplementary data to prove that we took care of patients. Incidentally.

I do disagree about cancer screening saving money down the road. JAMA published an article that cancer screening does not decrease all cause mortality. Annals of IM published another article that the cost of annual screenings in $43billion mostly driven by colonoscopy (and this does not capture any follow up cost). The data for colonoscopy is based on observational data and the only RCT (NORDIIC trial) did not show any benefit in people invited for colonoscopy.

Besides data collection issue, this creates a bias “for” screening. If we tell people about the NORDIIC trial, several people may choose not to undergo colonoscopy and that penalizes the primary care doctor (I am not against screening, I think people should make an informed decision).

As an independant primary care physician, I am trying to raise awareness about the financialization of medicine on my website www.PCPLens.com.

Looking forward to reading more of your articles.

It strikes me that so many of these problems would be substantially improved by surfacing quality measures directly to patients. This can be achieved by patient portals or third party patient-facing EHRs. It’s time we directly empower patients to take care of themselves. The ultimate incentive-alignment is a patient’s own health!

Perhaps health plans can devise ways to financially incentivize patients for meeting their own care gaps? Pay back a percentage of the money earned to patients.