The Clinical Innovation Mindset Stack

A framework for thinking differently about healthcare transformation

“Traditional business processes have the capacity to hide vast inefficiencies and problems without anyone noticing.” - The Toyota Way

Health tech has reached maturity. It’s not totally clear when this happened but at some point mid-pandemic everyone on LinkedIn started sharing logo maps attempting to organize our suddenly in vogue field - by services offered, by number of patients served, by total funding raised. Some might argue that it was also the height of the unbundling pandemic. No longer just an interesting “sell the dream” space, health tech now represents the innovation engine of healthcare broadly. Along with this maturity new organizational structures and roles have developed within health tech organizations, including the emergence of the Clinical Innovation team.

In this article, we sketch out the “Clinical Innovation Mindset Stack” and further empower those driving clinical innovation from within health tech organizations. Our perspective here is that of practitioners doing the work, trying out new approaches, and seeing what works. As we iterate on what’s working right now, we invite feedback on what works for others. We’ll describe the typical work of the clinical innovation team, the benefits of retaining a beginner’s mind with this work, “the stack” we’re using on a daily basis, and ways you can get started.

Let’s start with a quick working definition of clinical innovation: innovation and improvement that originates from within the clinical organization and advances at least one component of the Quintuple Aim of healthcare without compromising others. We are particularly interested in exploring clinical innovation from the perspective of healthcare delivery, where patients are the ultimate customer, though all of this advice is broadly applicable.

A couple of disclaimers:

Clinical innovation can also refer to a bunch of things that we’re not trying to write about here, including entrepreneurialism in health tech, technology or research advances in healthcare, and the function of acquiring new clinical and operational capabilities for your organization through vendor arrangements, JVs, or M&A. All of that stuff is awesome, but it’s not our focus here.

Innovation is of course happening everywhere throughout the organization. Innovation is a function of culture, not one team or role.

The People

The clinical innovation team may live in several different places within the organization. Here are some common arrangements:

Clinical Operations, reporting up through the Chief Medical Officer. This is probably the most common arrangement.

Operations, reporting up through the Chief Operations Officer. In this arrangement, the team may drop the “clinical” descriptor in exchange for something more general, like Performance Innovation or Care Innovation.

Senior Leadership Team, reporting to the CEO directly. This is particularly an option if the CEO is an MD or other type of clinician.

Clinical innovation team members could be a mix of clinicians (practicing in the organization or not), operations leaders with strong analytic and communication skills, and healthcare consultant-types who have found their forever home of a client. It is worth noting that the clinical innovation “team” may start off as one person, or even a fraction of one person’s role, and then develop as the organization grows.

The Work

So what’s the actual work of the clinical innovation team? Generally, clinical innovation is about problem-solving. Our advice to anyone just getting started in this space is to actively embrace problems. Problems are the main input of the innovation process. The clinical innovation team’s core work starts with deeply understanding the problems of your patients, the care team, and your business. Some questions to get you started:

What are the top 3 patient complaints?

Where are there bottlenecks and friction in a core workflow?

What workflows have a high rate of failure?

What does the care team describe as their biggest challenges?

What new services could we add that would drive health outcomes for our patients?

Being “solution-oriented,” as one finds in many job descriptions, is only half of the equation. First, we recommend being “problem-obsessed” so that improvement efforts are informed by a deep knowledge about the problem or challenge. Our advice: Go see the problem. Or even better, experience the problem. Clinicians who still practice are particularly well positioned for problem (read: product and customer) discovery and can leverage their role to surface insights uniquely available to them. The added benefit of clinicians feeling the “pain” firsthand is that they are motivated to develop and implement improvements that will make their own lives easier. If you can’t experience the problem yourself, then the second best approach is speaking with the patients and the care team members experiencing the problem or service gap. Get forensic and do some chart dives. Document what you learn in a way that tells the story of the problem. This approach is not just about identifying issues but also understanding the context in which they exist. The space between the patient and their healer is steeped in tradition and ritual. These elements, part of the 'way we've always done it,' significantly influence the nature of the problems you observe and the resistance to change. Recognize that you're navigating a landscape shaped by centuries of practice, where historical inertia plays a crucial role in how problems are perceived and addressed.

Teams that embrace many types of problems develop an appetite like that of an omnivore - they are comfortable eating whatever lands on their plate. A diverse problem diet is an asset as it will deepen the team’s understanding of the overall health of the organization and where its problem areas are. In any given quarter, the team will likely support a mix of operations-focused efforts, like launching a patient scheduling process or redesigning the onboarding flow, as well as clinically-focused efforts like launching new services and developing new protocols. The content of the challenge will change, but it’s all about solving problems. Developing a versatile, flexible problem-solving framework will help the team support innovation and improvement across the organization, no matter what’s on the menu. And context matters. Working for large corporations is like showing up at all-you-can-eat buffets while startups are more like potlucks where you BYOP (bring your own problems).

The Stakeholders

Healthcare organizations often refer to themselves as “patient-centered.” To really understand an organization’s commitment to this ethos, observe how empowered the frontline care team is to drive improvement and innovation on behalf of the patient. One of our most strongly held beliefs is that the best improvement and innovation work comes from the care team because they are closest to the patient. One of the essential functions of the clinical innovation team is to facilitate problem-solving in partnership with care team members by bringing structure to problem-solving conversations. Some examples: facilitating ideation sessions, helping the team design an experiment, making a workflow more visual by sketching it in FigJam, and setting up prioritization exercises, like dot voting or an effort-impact matrix.

Creating space for patients to add value as co-innovators is essential. The best innovation workshops often include all stakeholders, which can be hard to achieve in practice. There are a lot of ways to bring the patient’s voice into the room, like pre-recorded interviews or narratives from care team members about their patients. However, inviting an actual patient into the room/Zoom is often the right move and can be done with the right framing and support from the legal team. The value of patient representation is recognized by federally-funded programs. For example, Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) are funded by the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) and require at least 51% of the board members to be patients who are served by the community center. Researchers are evaluating the impact of patient advisory contributions on healthcare outcomes. Such findings could further drive patient inclusion and participation in care delivery innovation.

Beyond one-off workshops, continuous feedback from patients throughout their journey can support the organization’s improvement culture. This approach goes beyond outcome metrics like NPS or other satisfaction measures and invites feedback on any part of the patient experience. Checking for satisfaction at the end of a patient’s journey risks recency bias and likely misses the opportunity for micro-improvements in upstream processes, like intake/onboarding. Cultivating feedback across internal and external stakeholders is a necessity for survival and adaptability. Making it easy for everyone to provide feedback means simplifying the process, being receptive to feedback at multiple touchpoints, and ensuring that their input leads to tangible changes. Simple changes such as embedding feedback buttons in EMRs and patient portals can be a game-changer. Ultimately, when clinical teams feel a sense of agency to affect their work and patients take on a proactive role in their care experience, care delivery organizations become more responsive, resilient, and attuned to the needs of those they exist to serve.

The Mindset

The Zen Buddhist concept of Shoshin refers to having the mindset of a beginner, no matter how expert or advanced you may be. Beginners are also learners. Learning requires openness, curiosity, and humility. This is the essential mindset of those driving innovation.

In our experience, a key signal that you have a healthy innovation process is that there are moments of shared epiphany. It’s those moments where the room/Zoom volume gets loud with the team’s excitement about a breakthrough or a new idea that they want to try and everyone is smiling. This experience is the “runner’s high” of an innovative culture. These epiphanies don’t happen when everyone brings their “expert” mindsets to a challenge - or if they do, it’s way less fun to be a part of.

One way to practice this mindset is to ask questions that challenge your assumptions and invite exploration and curiosity rather than asking questions with the expectation that the answer will further prove your point or reinforce your current thinking. This may seem risky at first, exposing you as uninformed or naive. To start, practice it in low-risk settings and do it with purpose (e.g. what are you trying to understand more deeply?). Demonstrating your beginner’s mind also helps build a permission structure for others to do the same.

Sample questions to have at your fingertips:

How can I view this situation from another perspective?

What is the core issue I’m trying to understand here?

What am I not seeing that could be relevant?

Could you help me understand why you built it that way?

What’s the purpose of this step in the workflow or patient journey?

What are you hoping the patient does next?

What aspects of this workflow might be overlooked by those not engaged in it on a daily basis?

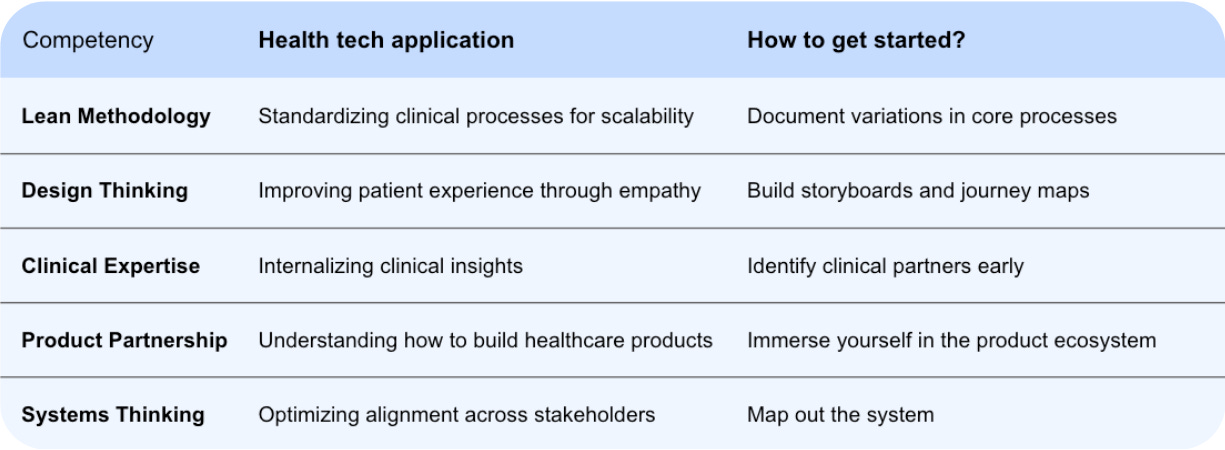

The Competencies

Establishing the right mindset for driving innovation is a prerequisite, in part because almost no one starts their career in clinical innovation with the entire stack under their belt. Much of this will be learned along the way. This stack is assembled from preexisting parts. The methods and frameworks we’re describing already exist and have proven effective in other settings. What we hope is unique and helpful is their synthesis and reframing in the health tech context. With that, let’s look under the hood of clinical innovation.

Lean Methodology:

“Without standards, there can be no improvements” - Taiichi Ono, originator of the Toyota Production System

Lean is a methodology for delivering greater value to the customer through continuous improvement and the removal of waste in core workflows. Many organizations practice lean in some form, but its application is highly variable from the casual fan to the orthodox practitioner. If you dip your toe in, you’ll quickly learn that lean is a deep pool of highly developed approaches, rival schools of thought, and strong opinions about “the right way” to do lean. Our advice: put on your innovator’s floaties, jump in, and figure out what works for your organization.

Lean has a long history of driving improvement in healthcare, though its origins are in car manufacturing. In his seminal book, The Toyota Way, Jeffery Liker describes 14 principles for developing a culture of improvement and building an organization of empowerment where teams ingest problems and metabolize them into innovation. Start with The Toyota Way - read it as a field manual, ideally with a colleague or two. You can also cruise through the resources on the Institute for Healthcare Improvement website.

How is it relevant to health tech?

In healthcare, we have standards of care. Lean applies that same rigor of promoting the best known way to all workflows, whether clinical or operational. Standards are the baseline for improvement and form a foundation that we can build on. Without them it’s difficult to gauge how new changes stack up against the status quo. Standards also create stability for the team and the patient, and scalability for the organization. Working in health tech can feel like you’re drowning in pilots, MVPs, and proofs of concept. This culture of innovation is what makes the field exciting, but it can feel disorienting and unstable if workflows remain duct-taped and pilot-y even as the business scales.

Lean’s focus on standards is a helpful counterweight to the dread teams may feel when the next “We’re launching another pilot! 🚀” email hits their inbox. The rapid iteration cycles common in startups are a feature and typically a signal of a healthy culture of innovation. Introducing standardization to that innovation cycle will support deployment and scaling of innovation work. An interesting parallel exists in how the DevOps methodology accelerated the speed and agility of software deployment in large organizations (“10+ Deploys Per Day” kicked off this movement and The DevOps Handbook is a modern guide for achieving this).

How do I get started?

Our advice is to start with a core workflow that is performed with variation and develop Version 1 of the standard workflow. Variation implies that there is no standard for doing the workflow. One of the fastest ways to discover variation is to have team members watch one another work and discuss what they learned afterward (institutionalized as “facilitated practice” at ChenMed) - an experience that often disappears for physicians after residency. The variation you observe can be viewed as a short-term asset – it represents a series of unintentional experiments conducted by the team to determine the most effective workflow. Version 1 of the standard workflow is likely hiding in the team’s variation. The first step is to align on what the workflow needs to do for the patient or the care team. In other words, what value does this workflow need to deliver? Once you can answer that question, you’re looking for the workflow that delivers that value in the simplest, fastest, safest, and most repeatable way. The documented variation now becomes Version 1 of the workflow, which needs to be disseminated to build consensus for adoption.

Design Thinking:

“But people aren’t cars!” This knee-jerk critique of lean and its origins in car manufacturing comes up sometimes. It’s likely a reflection of someone’s experience with a poorly implemented lean program or just a lack of familiarity with lean. Nevertheless, design thinking pairs really well with lean, particularly in the context of human-centered sectors like healthcare where lean can seem like an incomplete approach. Lean and design thinking share many of the same principles even if the specific language is novel to each. A short list of examples:

The belief that those experiencing a problem hold the insight to unlocking progress.

The importance of understanding the end-to-end workflow from the perspective of those doing the workflow and experiencing pain in the current state.

The belief that progress happens through cycles of learning achieved typically through iterative experimentation and a mindset of curiosity.

Design thinking translates the “patient-centered care” ethos into action by providing a framework for putting the patient at the center of the design process. Design thinking anchors the innovation process in active empathy for the patient by immersing innovators in real observations of the patient experience. The patient voice is not relegated to an end-of-funnel feedback survey, but rather an upstream, pre-design stakeholder voice. The design thinking method is fairly well established and IDEO’s method is considered the method.

Begin by framing a question to focus your team on understanding the real needs of your customers, and then seek inspiration through observation and discovery. Use this inspiration to generate innovative ideas, build and test prototypes, and upon finding the right solution, share the story with your stakeholders.

Like any method, there’s the version described in clear, discrete steps and then there’s the reality of its application. The design thinking method is not a set of instructions for “executing innovation” but rather a guide for orienting teams as they move through the phases of innovation. It’s helpful to know which step you are on and what is likely the right next step, but you may choose to move backwards as you learn more or you may (gasp!) choose to skip a step when the pressure of delivering in a startup environment requires it. Though, word to the wise, don’t skip the “Test to Learn” phase. You can shorten it, but be cautious in skipping it.

How is it relevant to health tech?

Design thinking scales well. Regardless of how many patients an organization serves and how much revenue it generates, the design thinking method draws your attention to subjective patient experiences and observations about real patients and care team members. Growth and success can sometimes trick us into thinking that we already know what the patient needs and what they value in our product. Practicing design thinking and its active empathy will keep us close to the patient experience and help us avoid slipping into a closed, expert mindset.

Design thinking also brings a fresh perspective to legacy problems. Is there a more legacy problem in healthcare than wait times? Waiting rooms are as synonymous with healthcare as white coats. Children playing “doctor” typically start the narrative in the waiting room. To reduce wait times, many organizations reach for the lean playbook, which helps reveal root cause drivers like schedule design, appointment start times, and patient wayfinding.

Here’s where the design thinking + lean combo gets really cool. If we get closer to the patient in that waiting room, we might learn a little more about their experience. No one wants to wait, so there’s no reason to overthink the value of reducing wait times. Allowing ourselves to be curious about the needs of the patient in the waiting room could lead us to deeper learning about the patient’s experience. Perhaps we even figure out how to get rid of the waiting room?

Here are some questions a design thinking mindset may lead us to asking:

What is the patient worried about as they wait?

Is this their first time seeing their care team?

Do they have concerns about insurance or cost?

Do they have someone with them in the waiting room? If so, who are they and why are they there?

Did they just come from a blood draw or imaging and are carrying with them information for the care team?

Design thinking helps us explore problems more deeply, particularly when elements of those problems are difficult to measure. Wait times are a great problem for lean as they are highly measurable. Design thinking gives us permission (requires us even) to explore questions that are less measurable - feelings, perceptions, the why behind human behavior.

How can I get started?

To better understand the method, we recommend starting with IDEO’s generous list of resources for facilitating activities and explaining concepts. You can also download their field kit for free (how is this stuff free?!). We also love Oscar’s approach to collaborative storyboarding described in this Medium post. This is a great example of a team going through the design thinking process and expressing what they learned through a journey map. It’s also a relatable story from a well-known OG health tech organization. The Oscar team does a great job of describing their method. Also, here’s the IDEO guide for creating a journey map - with a healthcare example to boot.

The other really thoughtful thing that the Oscar team did is that they developed a fictional patient, Gina, and built the workflows around Gina. You don’t necessarily need to hire an illustrator like the Oscar team did, but sketching out visual representations of your patients is a good way to force yourself to really think about your patient and represent them visually. Empathy mapping is a great way to bring your patients into the room. Here’s IDEO’s empathy map guide.

Design thinking has become a social technology that helps us not only ask more impactful questions but also transforms us as innovators in the process of deploying it. By learning how to challenge our own assumptions, we guard against biases that constrain our perspectives.

Clinical Experience:

Health tech innovations are changing the way healthcare is delivered. A hybrid experience is emerging where some things happen in person and others happen virtually. Even with these changes, most care is still delivered by a person in an exam room, surgical suite, or pharmacy anteroom. Every clinician working in health tech today was trained in person in a hospital setting. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave is relevant here. If we do not understand how traditional clinical medicine works, we’re inferring what it might be from the shadows on the wall. We need to get out of that digital cave and into the clinic. There is a lot of wisdom accumulated in the clinic setting: anticipating unintended consequences, downstream effects, and insights about patient behaviors and expectations. For example, primary care physicians have a distinct advantage in grasping the subtleties of care transitions due to their training in various environments. Their experience spans initiating referrals from outpatient clinics and urgent care centers to managing patients referred to them in hospital and emergency room settings. Such experiences give insight into when it may be premature and unnecessarily costly to send a patient to the ER while recognizing when it’s prudent to not delay escalation of care. Clinical decisions are often intertwined with decisions of capital and resource allocation in the real world where medicine is not immune to the laws of business. Having access to clinicians with expertise in end-to-end continuum of care can be a differentiating factor for startups building next generation tech-enabled healthcare services.

How is it relevant to health tech?

Health tech, at its best, is about disrupting thoughtfully evolving healthcare. If you are coming to health tech from another space, then it is particularly important to commit yourself to understanding the practices and patterns of the clinic. This will build trust and accelerate your work. It will also help you identify some of the friction points we’ve imported from the old days that still need creative problem-solving. Patient scheduling and capacity management are still necessary even if exam rooms are sometimes Zoom rooms. Patients who join appointments virtually may have the same expectations for care as those who arrive in person even if their needs are different. We still care how much patients wait before an appointment, even if there is no waiting room. And as much as health tech wants to eliminate the waiting room, it’s important to understand what it’s replacing. For example, in rural communities, waiting rooms are often the locus of socializing. It’s the rare opportunity for neighbors to catch up with each other or bring home-grown tomatoes to their doctor as a sign of gratitude for their trusted relationship.

Non-clinical founders are strongly encouraged to team up with their clinical counterparts. Having the right industry insight from the beginning can prevent many early pivots and avoid unnecessary distractions (Primary VC hosted a fascinating discussion from seasoned founders on this very topic). Onboarding clinical talent brings not only their subject matter expertise, but also their clinical networks from years of training, practicing medicine, and experience in endless pain points in care delivery. Valuable lessons are learned by practicing medicine that cannot be gleaned from simply passing multiple choice exams that grant the “MD” title. Access to guidance from clinicians in the trenches is a competitive advantage to health tech builders. Some investors even argue that more physicians should be health tech CEOs.

How can I get started?

Ideally shadow clinicians in-person to soak it all in. Talk to them about their training and identify gaps in resources and explore the principal-agent problem that is pervasive in healthcare. If medical shows are going to be your curriculum, Scrubs is the closest to real life. Lean heavily on the beginner’s mindset. Ask about anything you don’t understand: exam room layout, the sphygmomanometer ritual, the flow of money, documentation requirements, or any strange acronyms (e.g. what does SOAP or MEAT mean?).

Consider exploring low-tech and no-tech innovations that can be equally impactful. For example, the Patient Priorities Care (PPC) clinical framework optimizes patient care by hyperfocusing on patient-defined goals (known as “The One Thing” at Devoted Medical) to guide all healthcare decisions. This model does not require transformative technology and relies on millennia old innovation: communication. Standardizing a workflow like this across most EMRs or even paper charts is a piece of cake compared to navigating interoperability at Epic. Successful execution involves task management across the care team in supporting the priorities of patients. Improvements in objective metrics for diabetes, hypertension, and congestive heart failure management back up the innovation rhetoric for PPC.

Product Partnership

Understanding the role of the product team is crucial and may not be intuitive for those coming from traditional healthcare settings. It would be a mistake to think of your product team as equivalent to the IT Team or an internal EMR specialist team. The product team decides what does, and more importantly, does not get built in the first place. They are one of your key stakeholders and partners in driving innovation in your organization.

Similar to the way product managers exert influence over internal stakeholders without having direct authority, clinical innovation teams leverage their unique insights and position to ship “innovation.” Both positions conduct user and stakeholder interviews. They also interface with software engineers and designers. This is critical because clinical and operational know-how guides what code is written and informs the ultimate design experience for patients or clinicians. You can’t automate a highly variable workflow. The clinical innovation team can help drive standardization, which then enables the product team to support automating parts of the workflow and return time to the care team.

How is it relevant to health tech?

Depending on what your organization is up to, the product team may be developing internal products (an internal EMR, revenue cycle widget or a communications platform) and externally facing products (e.g. an app for patients or caregivers). Consider the administrative burden in healthcare that plagues patients and clinical teams alike. Primary care presents some of the most interesting opportunities for care transformation for product-minded innovators. The entire specialty has become a catch-all for all patient related admin tasks. Most specialists turf responsibility for patient needs outside of their specialty’s organ system to “follow up with PCP.” This heavily administrative “privilege” is not matched with access to project management tools for PCPs. Traditionally, the tools physicians use (e.g. EMR) have been designed to service billing requirements. Virtual primary care trailblazer, Dr. Jay Parkinson, has illustrated that many of the basic things we do in medicine can be thought of as projects. For example, UTI requires a few days to manage until resolution, pneumonia - a couple of weeks, and breast cancer - many months. Pairing insights to administrative needs with product expertise can accelerate the solutions that clinical innovators roll out. Having a strong product partnership ensures that such iteration cycles align to stakeholder value.

How can I get started?

Meet people in product: designers, product managers, and chief product officers. Ask to shadow them to understand how they frame problems and spot opportunities. You’ll notice that product leaders anchor the innovation process by continuously reconnecting the day-to-day building work back to the core problem they are trying to solve for patients or care teams. Take Product Management courses, such as Product Management Basics from Pendo and Mind the Gap, to learn core concepts. Read industry classics such as Escaping the Build Trap and Inspired to appreciate the product development philosophy. Join industry communities like PMs in Healthcare to connect with fellow builders and innovators. Immerse yourself in the world of product, not necessarily to become a product manager, but to gain appreciation for the user-centered approach product teams bring. The goal is to learn how product pros think so you can better partner with them. Their skills will strengthen your innovation ecosystem.

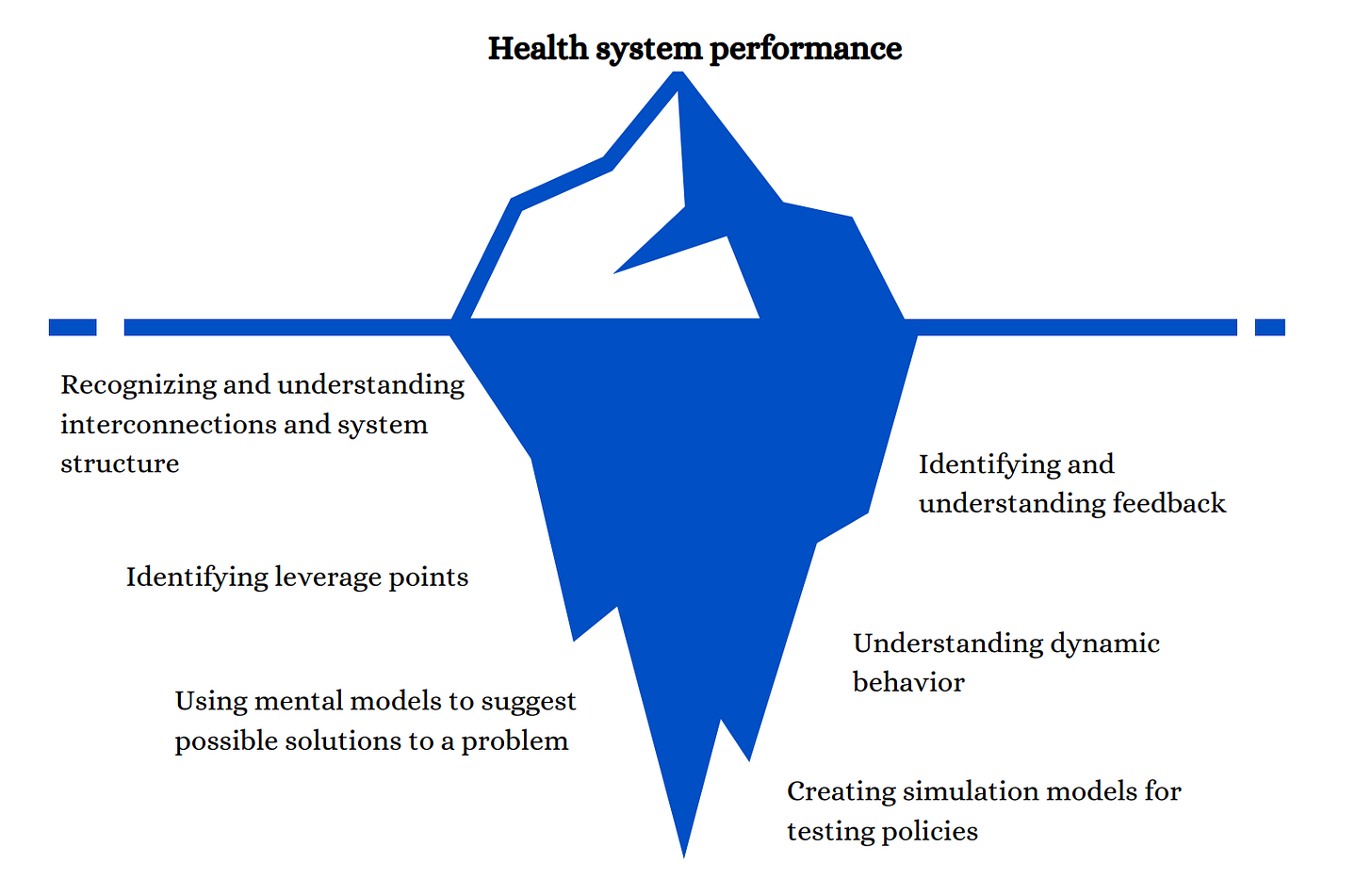

Systems Thinking

“Today’s problems come from yesterday’s solutions.” - Peter Senge

It’s inevitable that some of the innovations we ship will cause unintended consequences. The only way to decrease the odds of unwanted future friction points is to apply a systems thinking approach to the totality of our interventions. This way we can guard against siloed thinking and short-term horizons. The key insight here is to consider second and third order effects of initial actions. We do so by examining interconnectedness of all components and meticulously thinking through how they might influence each other. In this process, we consider all stakeholders and the impact of our solutions on their experiences. Part of the strategy is proactive reflection that helps anticipate which groups of stakeholders might be adversely affected and which processes will require course correction.

How is it relevant to health tech?

Systems thinking in health tech is about understanding and optimizing the complex web of interactions in healthcare delivery. Distribution and integration are the two major bottlenecks for many healthcare innovations and products. Identifying what forces (e.g. regulatory, technical, or financial) influence their adoption is part of the puzzle when operating in an opaque system. It’s rare for incentives in healthcare to be aligned, which causes frustration among innovators when their rational solutions don’t gain traction. Identifying entrenched behaviors through a systems lens is one way forward. Considering the ripple effects of each novel intervention among a multitude of stakeholders is what makes clinical innovation both bewildering and exciting. For those building point solutions, consider how each patient flows into and out of your ecosystem.

For example, value-based systems take on risk and are incentivized to reduce costs for avoidable expenses, such as inappropriate ER utilization. Innovations with a systems perspective would consider alignment across many domains impacting a patient’s decision to go to the ER, such as:

primary care access (PCP not available)

care navigation needs (not knowing where else to go)

medication costs (seeking rescue medications in ER due to inability to afford maintenance treatments)

health literacy (not understanding what ailments can be managed outside of ER)

financial literacy (not understanding cost implications of frequent ER visits)

transportation limitations (ambulances take patients only to ER)

food security and housing stability (ER offers a snack and temporary shelter)

How can I get started?

Start by mapping the system you’re innovating within. While there are many frameworks for this, the Systems Thinking for Health Actions (STHA) is fairly comprehensive and approachable to beginners. The process begins by identifying system components and tracing feedback loops. This will provide an overview of the variables that your work will influence.

Learn how to recognize and stratify leverage points. Donella Meadows’ framework illustrates how the deepest roots of a system shape its surface-level structures. Identifying higher leverage points such as value systems is integral to transformation work, but is much harder to affect compared to influencing lower leverage points such as information flows.

Finally, learn how to predict system changes over time through experimentation. If you get this far, you’re bound to be tempted to build simulation models to test your theories of change.

Parting thoughts

The Clinical Innovation Mindset Stack offers a framework for thinking differently about healthcare transformation. Here are the key takeaways to remember:

Stay grounded in the lived experiences of patients and care teams. Continuously gather observations and insights from the frontlines.

Take an iterative approach. Design thinking and lean methodologies promote cycles of rapid experimentation and learning.

Foster strong partnerships with product teams. Align innovation efforts to core stakeholder needs.

Immerse yourself in clinical environments. Draw inspiration from traditional care delivery, but challenge the status quo.

Adopt systems thinking. Consider downstream effects and unintended consequences.

While frameworks provide structure, innovation remains an art. It ultimately requires creativity, empathy and a willingness to rethink assumptions.

Practicing the Stack in the madness of a startup

Even for folks working in clinical innovation roles, not every moment of work life is filled with the thrill of experiments, epiphanies, workshopping, and ideation. It’s almost always mixed in with the typical planning meetings, huddles, and operational projects. And for those in clinical roles, actually caring for patients. Speed and time (i.e. funding) is often highly valued in any startup, health tech included. You may not have the leadership support or the time to do things the ideal way. Drawing on your wisdom from using the Stack to pull the right tool, concept, or exercise is very much part of clinical innovation in a fast-paced startup.

Beware that an alternative innovation pre-requisite may exist for mature organizations without a previous innovation role. While an innovation lead can be brought in to “innovate,” they may really be needed to fix all the duct tape that’s barely holding things together. Even the best innovation work won’t sustain unless there is a solid foundation to build on. Patience is key in this scenario.

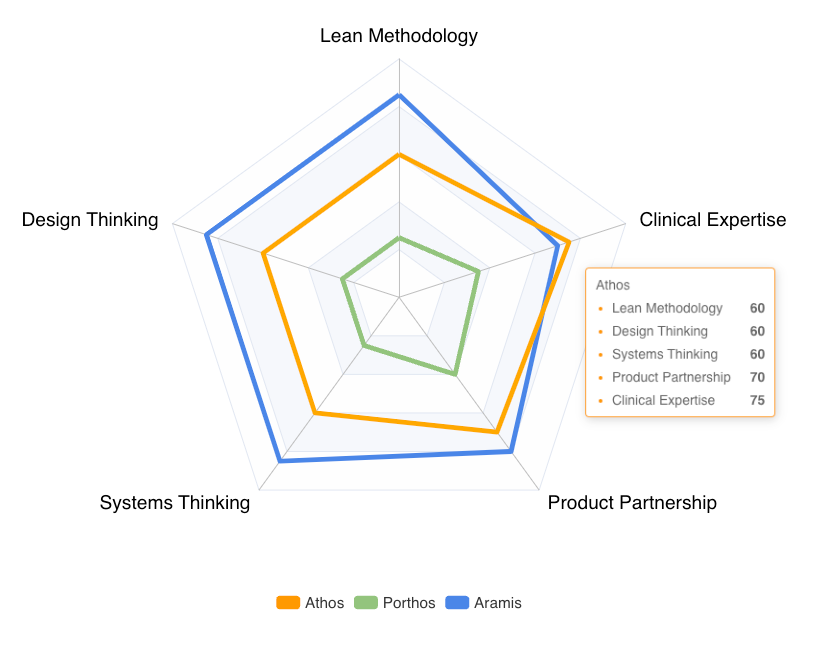

Evaluating the Stack

As our field matures, leaders of clinical innovation teams will require tools to evaluate their colleagues across competencies of the Stack. While criteria to measure progress within each competency is yet to be determined, we propose scorecards to track individual and group performance. These insights can be used to refine curricular developments and identify emerging rockstars as well as those that will require extra coaching.

Teaching the Stack

At some point, an organization’s need to problem solve and innovate, will scale beyond the capacity of the current clinical innovation team. The organization can either continue to grow the team to keep pace, or create a learning and development strategy for empowering everyone in the organization to problem solve and innovate. This pivot may come later in the organization’s development (think Series D and beyond). Building agency and problem-solving skills across the organization is key to sustaining innovation.

Go forth and innovate! And let us know how it goes.

Paulius Mui, MD is the Director of Clinical Innovation at Next Level Medical.

Ben Dolson is the Director of Clinical Performance and Innovation at Twin Health.

“Lean heavily on the beginner’s mindset. Ask about anything you don’t understand: exam room layout, the sphygmomanometer ritual, the flow of money, documentation requirements, or any strange acronyms”...

This resonated with me. College is constantly teaching students that speaking more / raising your hand more is better performance. During job applications, we have to constantly try to convince people of all the stuff we know. But, I have noticed that the real world rewards people who admit they don’t know enough and need more info.

This is true especially for Healthcare. Any successful innovation that I’ve seen has started with people admitting that they don’t know enough and need to conduct more research. Leaning on the beginners mindset is definitely the key.

Love this Paulius and Ben! I wish I had had this article when I started as Senior Medical Director of Clinical Innovation at Clover!