What Does Good Care Look Like?

Exploration of tradeoffs across stakeholders

Exploring the depths of what good care means with Alexandra Ristow, MD has been a treat. Alex is a primary care physician and executive with a passion for building innovative processes, technologies, and patient-centered care models. She’s on the lookout for her next opportunity so reach out to her if you’re growing your team.

We invite you to sign-up for the upcoming virtual XPC IdeaFest on Nov 1 for hands-on problem solving about what “good care” means.

A patient asks her primary care doctor to recommend a “good cardiologist who will listen.” A hospital system allocates scarce resources to a fall-prevention campaign. A clinic director shortens visit slots to allow for better access (and margin). A startup creates an automated onboarding process to increase scalability.

In each scenario, someone has explicitly or implicitly answered the same unspoken question: what is good care? The answer to this question determines how we train clinicians, what processes we build, and how we allocate time and money. But in a system with limited resources and countless stakeholders, how do we align on this definition?

In this article, we explore:

Why stakeholders in healthcare each have unique insights and blind spots on the question of good care

Key tensions and tradeoffs when thinking through good care

Case examples to illustrate how the same care may represent a success or failure to different stakeholders

Why stakeholders can mean well but think differently

Ask five New Yorkers what makes a good pizza and you are likely to get (at least) five different answers. Healthcare is no different. Not only is healthcare subject to the same subjective preferences of any service industry, the number and diversity of stakeholders involved in healthcare is staggering. Each of these stakeholders has their own values that inform what they believe good looks like and what tradeoffs should be made.

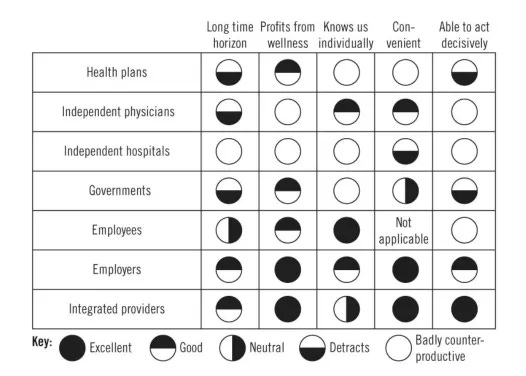

Imagine we were determining how to measure “good care.” We would need to first agree on a few basics. Before even getting to the meat of what “good” means, we run into diverging stakeholder opinions (Figure 1). What timeline do we measure over? Who is the focus of our measurements - individuals, panels, communities, countries? Patients, payors, and health tech companies are likely to think in terms of 1- 3 year intervals for reasons of human bias, payor churn, and funding runways. Policymakers or primary care clinicians may think in terms of decades or even generations. Patients and clinicians are more likely to try to prioritize individual outcomes, putting a premium on patient autonomy and individual optimization. Health systems, payors, and policymakers think about optimizing outcomes at a population level. As for the definition of “good,” each stakeholder’s unique vantage point comes with special insights as well as blind spots.

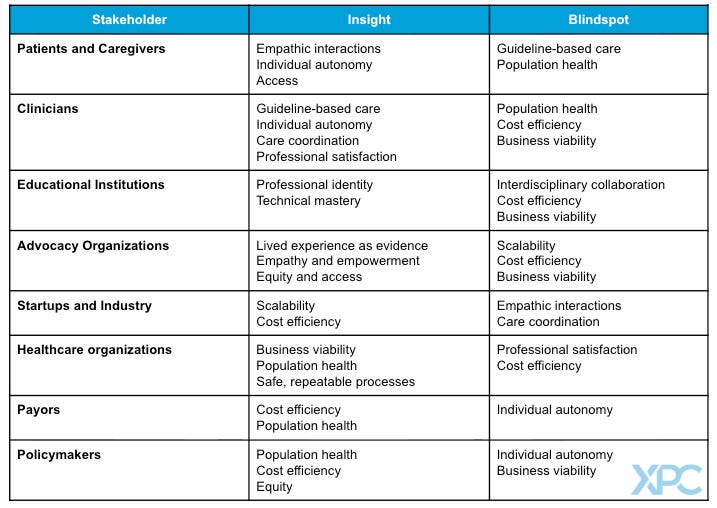

The insights and blind spots of healthcare stakeholders

Healthcare’s stakeholders can roughly be divided into three groups: people, organizations, and industry. Each stakeholder views good care through a different lens, affording both unique insights and potential blind spots.

People

Patients

The majority of stakeholders provide or administer healthcare. Patients experience it. This is a unique vantage point in healthcare, and it has often been undervalued. Patients are not a monolith, but when they are asked about what makes good care, three broad priorities consistently emerge: interpersonal connection; access to visits and assistance between visits; and structural elements such as affordability, wait times, and even parking.

For decades, the medical community treated the patient experience as a “nice to have,” separate from the technical elements that were deemed to determine good care. This was a mistake. Patients’ experience of care directly impacts the results of their care. For example, patients consistently say that good care makes them feel respected and is rooted in a strong, caring relationship. This is not just a preference, it has real consequences: patients with higher trust in their clinicians show more beneficial health behaviors, have more confidence they can impact their health, show higher self-efficacy, and report higher quality of life. Patients also prize care that is individualized to their circumstances over care they may feel is more routine or impersonal. Again, this preference impacts outcomes: patients whose care plans reflect their unique context are more likely to improve, an effect seen in outcomes ranging from lung function to depression symptoms.

While relationships and individualized care matter deeply, other factors sometimes outweigh them. The popularity of the urgent care model as well as direct-to-consumer telehealth platforms such as Hims and Hers, Ro, and Wisp show that for some situations ease of access and transparent pricing matter more than a long-term relationship.

Patients do have blind spots. Most patients do not have the clinical knowledge to judge the technical elements of their care (Was that the right diagnosis? The first-line treatment?). Patients do care about clinical quality, but they must judge through proxies such as how trustworthy they found their clinician, the name brand of an institution, or overall service quality. While patients may be cost-sensitive for their own bills, they generally do not consider the allocation of limited resources across a population when thinking about the quality of their own care. For example, a patient whose insurance covers an extra hospital night may define good care as “staying to be sure” without having to consider who else may need the hospital bed or the societal cost of an extra night that does not have a clear medical indication.

Patients, particularly those with complex needs, often rely on family members or friends who coordinate or deliver informal care. These caregivers experience the healthcare system slightly differently from patients themselves. For caregivers, navigation, communication, and structural ease become even more critical to good care. Caregivers are often the ones scheduling appointments, managing medications, and handling paperwork for a patient– and this work is on top of the caregivers’ own career, parenting, or personal health obligations.

Clinicians

Clinicians spend years mastering their clinical skills and decades embedded within complex healthcare systems. It is not surprising, then, that their perspective on good care often emphasizes clinical and technical skill, effective care processes, and organizational support. Their training gives them unmatched expertise in defining the clinical and technical components of good care. Indeed, professional organizations spend countless hours creating and updating specialty-specific practice guidelines and recommendations to define good care. Yet clinicians, too, have blind spots.

Most clinicians care for one patient at a time, and they understand that part of their value is adapting the science and the guidelines to the unique person in front of them. This creates complexity when trying to identify good care at a population level, as there are always exceptions to every guideline or best practice. Additionally, clinicians are generally not trained or reimbursed to think about the outcomes of their patients as a panel. Although value-based care and quality metrics now encourage population-level thinking, a clinician’s predominantly visit-based calendar and reimbursement structure anchors them in a 1:1 practice. A clinician’s focus on understanding the needs and goals of one patient at a time - as well as a need to maintain rapport and prioritize among many issues - often creates tension and resentment when clinicians are told to meet population-level goals to meet standards of “good care.”

For example, a doctor may believe in screening mammography, but when told to try to get her screening rates from 80 to 85% she may feel dispirited and disempowered, citing patient choice, the unique demographics of her panel, socioeconomic barriers like transportation she cannot control, and insufficient time to provide all guideline-directed care. Asking clinicians to consider cost at population level in their care decisions for an individual meets with even more resistance. On the one hand, clinicians generally agree that they should adhere to guidelines that discourage marginally beneficial care. However, 85% of clinicians reject the idea of denying beneficial but costly services so that resources can be redirected to patients that need them more.

Finally, physicians are at risk of forgetting that the outcomes that they care about physiologically, such as Hemoglobin A1c targets, are often meaningless to patients unless they are tied-in to goals that the patient values, such as function or independence. Clinicians may discount the importance of providing clear information to patients and families. They may overvalue the importance of what happens in the exam room and operating suite and undervalue the importance of support, education, and coaching between appointments.

Increasingly, care is delivered not by solo clinicians but by interdisciplinary teams. These teams broaden the definition of good care by increasing the value of seamless care coordination, communication, teamwork, accountability, and whole-person care that addresses mental, physical, and socio-economic factors. A team can often support patient self-management, proactive check-ins, and panel-level management in a way that is not feasible for a solo clinician. Different members of the team may have different definitions of “good care.” Specialists often define quality through precision and mastery of their domain, often specific to an organ system; primary care clinicians, in contrast, think about whole-mind-body, preventative care that is integrated into a patient’s life and context.

Organizations

Educational institutions

Universities and professional schools play a central role in shaping how future health professionals think about “good care,” yet they often present a limited view. Most programs disproportionately emphasize a single element of the biopsychosocial model, reflecting what they feel to be the needs of their cohort. Medical and nursing schools focus on the biological and technical aspects of disease; psychology and therapy programs focus on mental health; social work programs highlight socioeconomic determinants of health. Each discipline develops expertise, but in isolation, leaving them with gaps in understanding of how to provide holistic care.

Interprofessional education may also take a back seat, as the goal is to achieve depth within a discipline rather than a broad understanding across fields. Students may have brief exposure to team-based care, but meaningful, sustained opportunities to train alongside other disciplines are rare. As a result, graduates can enter the workforce unaccustomed to the teamwork and communication that other stakeholders see as integral to good care.

Finally, educational institutions still train students to manage individual patients, one encounter at a time, rather than to manage the health of an entire population. While some schools incorporate lectures on population health management or the economics of care delivery, the opportunity to see or apply these ideas in practice are rare.

Advocacy Organizations

Advocacy organizations represent the interests of specific patient communities, often defined by a particular disease, condition, or identity (e.g. National Brain Tumor Society). Their primary imperative is to amplify the patient voice and advance the needs of their constituency. For them, “good care” is defined by the lived experience of the patient - it must be deeply patient-centered, responsive to individual goals, and ensure access to the most effective treatments. This perspective extends beyond clinical encounters to encompass social support, education, and empowerment as integral parts of care.

This unwavering focus on a particular population’s needs can put advocacy groups at odds with other stakeholders. Their calls for rapid access to new therapies or specialized resources may conflict with the cost-containment priorities of payors, the standardization imperatives of health systems, or the evidence thresholds of policymakers. Moreover, their success in raising awareness and attracting funding can create a competitive environment for finite resources, where compelling narratives and organizational visibility determine which conditions receive attention.

At the same time, advocacy organizations play a crucial integrative role in the healthcare ecosystem. They connect individual stories to system-level change and translate patient experiences into policy, research agendas, and public awareness. When aligned with other stakeholders, advocacy groups can help bridge the gap between what the system delivers and what patients truly need.

Health systems

Health systems are quite heterogenous, but they typically consist of an affiliation of healthcare organizations that include at least one acute care hospital and one primary care group. (Many other definitions exist.) Whether non-profit or for-profit, health systems are medium to large businesses with a survival imperative: grow the patient base, operate efficiently at scale, and balance the budget. These pressures shape how they define “good care.”

For a health system trying to sustain a market foothold, good care must drive growth. Access, in particular for new patients, takes on high importance for its impact on both patient experience and growth. But easy access can come at the cost of time with clinicians and continuity with a trusted provider, eroding the trusting relationships that clinicians and patients prize. Health systems do invest in service-quality initiatives such as AIDET to boost patient reviews and retention, yet the need to staff flexibly across departments and shifts often fragments the patient experience into many fleeting encounters.

Scale brings another bias: good care must be safe and effective across large, complex systems. Systems aim to minimize errors and produce repeatable outcomes across large populations; health care systems must also hire, train and then sustain the performance of large numbers of staff. This creates a bias that good care must be embedded in strong processes rather than relying solely on good people. While a focus on system and process is critical for safety, it can clash with patients’ and clinicians’ desire for individualized goals and care. A health system’s push to reduce variability among processes can impinge on individualization and connection by creating too many clicks, too many restrictions on care pathways, and too many distractions from the patient-clinician interaction.

Because of the sheer volume of patient interactions, health systems define and track outcomes at the population level. Population-level data help keep operations focused, but the need to rely on high level metrics can flatten the nuance of care. It is easier to track length of stay than it is to track whether the care was appropriate for the patient’s context or goals. What is tracked gets focus; what cannot be tracked at times gets forgotten.

Finally, financial realities drive a bias towards reimbursable care, which often means more care, especially while fee-for-service remains dominant. Although researchers and policymakers advocate for primary care to be the quarterback for most patients, health systems have incentives to route patients to more (and more highly-reimbursed) clinicians. Activities like care coordination or patient advocacy, which many stakeholders view as essential to good care, receive little emphasis because they generate little revenue. Just look at the calendar of a typical physician in a health system; the vast majority of their time is earmarked for back-to-back visits, with little (if any) time dedicated to coordination or advocacy activities. Alternative payment models attempt to tie payments to quality and might shift some of these ingrained incentives; however, the underlying architecture of care delivery remains fee for service.

Private Payors

Payors are generally medium to large businesses managing very large patient populations. However, in sharp contrast to the health systems whose revenues grow with utilization, the payor’s business imperative is to control healthcare costs. For them, good care must above all be cost-effective. This aligns with policymakers concerned about the burden of rising healthcare spending on society, but it also introduces distinct biases.

Payors’ emphasis on cost-effectiveness is often at odds with other stakeholders’ values. Narrow networks, theoretically designed to steer patients towards high-value clinicians, encroach on patient choice. Utilization management mechanisms such as prior authorization or step-therapy, intended to prevent unnecessary or low-value services, can cause delays or create administrative burdens that frustrate both clinicians and patients.

Payors also prioritize interventions that yield near-term savings. Members rarely stay with the same private insurer for long, on average as little as 2 years and typically less than ten. This churn means that investments whose payoff is delayed by decades, such as intensive childhood obesity programs, may be harder to justify when the financial benefits may accrue to a competitor.

Private payors’ focus on quality and performance is heavily shaped by federal standards. Most commercial insurers mirror the metrics and incentives set by Medicare and Medicaid through programs such as HEDIS (Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set) measures or CMS Star Ratings. While private payors retain flexibility and may innovate beyond public program requirements, many default to equating “good care” with these population-level benchmarks for preventive services, chronic-disease management, and readmission rates.

Policymakers

A diverse group of organizations contribute to healthcare policy in the United States, ranging from Congress; federal agencies such CMS, the FDA, the CDC; state governments; professional associations; lobbyists; and independent task forces. Each operates with its own set of incentives and biases, biases which may shift as leadership or political winds change. Historically, agencies like CMS, the CDC, and national task forces were viewed as well-positioned to balance considerations of scientific evidence and fair resource allocation across large populations and across longer time horizons.

However, biases exist. Elected and politically appointed policymakers may favor policies that reflect the ideology of their base and interventions that will create impact during their terms, often just two to four years. Policymaking is also an exercise in compromise: competing interests force negotiated solutions that can result in complex, sometimes contradictory regulations. Because policymakers rarely implement these directives themselves, they may underestimate or tolerate administrative complexity that places a burden on clinicians or health systems. Finally, when thinking across such large populations, policymakers often prioritize perceived public good over individual choice as most essential for good care.

Industry

Health tech companies

Health technology companies can bring fresh perspectives to a healthcare industry that is historically slow to change. Startups that serve patients must be highly attuned to patient preferences in order to attract and retain users, and many are born from a single pain point identified by patients, clinicians, or payors.

However, start up culture and the reliance on venture capital create their own biases. Startups favor fast, disruptive innovation over incremental change, which means the care or products they deliver sometimes outpace the evidence for safety and efficacy (see the book Careless People). To avoid complexity, startups often start with a focus on a very limited number of problems or health conditions and may go direct to consumer; while the episodic care they provide may be useful, this often leads to overall fragmentation of a patient’s healthcare experience and erosion of their longitudinal care relationships.

Venture capitalists expect exponential growth and short-term profitability, adding to pressure on health tech companies to cater to customers’ needs, particularly those needs that are faster to solve. Providing quick access or offering care that may stretch or sidestep standard practices, such as extensive hormone testing or unproven longevity treatments, is much quicker to deliver than coordinated, relationship-based care. Scalability itself becomes a core definition of good care: services must be tech-enabled, repeatable, and scalable at low marginal cost. This growth imperative can undervalue the slower, less-scalable human elements of care such as relationships, nuanced clinical judgment, and shared decision-making.

Pharma and devices

Pharma and device companies drive important innovation in clinical care. Through extensive research and development, they bring to market products that can improve or even revolutionize the care patients receive. However, their business model shapes how they define good care. By nature, they bring a bias that good care requires long-term medications and devices more so than processes, relationship-based care, risk-benefit discussion, or lifestyle interventions that can at times be equally or more effective.

The patent and regulatory environment rewards novelty, creating strong incentives for pharma and device companies to define good care as the newest drug or technology. This can lead to “me-too” drugs or iterations that provide only marginal incremental benefit at exponentially higher prices.

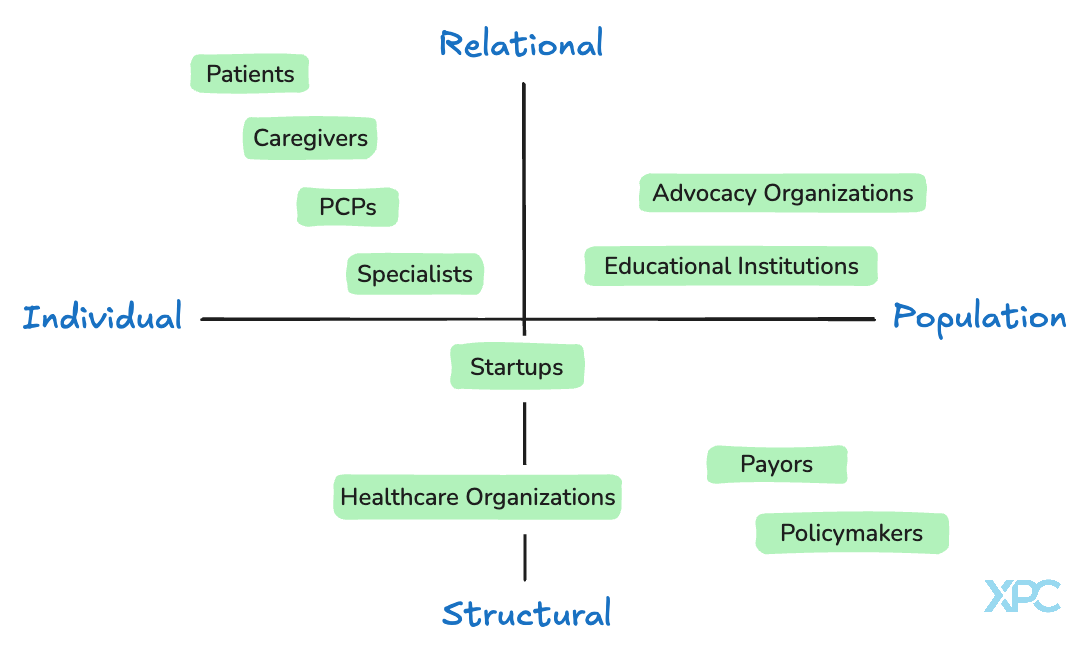

Another way to think about the multitude of perspectives on “good care” across healthcare stakeholders is to frame them on a simple 2x2 matrix (Figure 2). Patients, caregivers, and clinicians focus on individual relationships and what happens in the room between people. Policymakers, payors, and educational institutions, think in terms of systems, rules, and populations. In between are groups like startups and health systems that try to bridge the two, scaling what works while keeping care personal. Each group brings something essential, but also carries blind spots. Seeing them together helps explain why the system often feels disjointed and where the opportunities lie to connect the human side of care with the structures that sustain it.

Some key tradeoffs

Any definition of good care will require tradeoffs. The combination of stakeholder opinions and actions has shaped the current state of these tradeoffs, whether or not we as a society have explicitly made a choice. We will explore a few of these tradeoffs; many others exist.

Present versus future outcomes

Modern healthcare has evolved with an implicit bias toward short term outcomes. Long term outcomes are harder to track and harder to link to a specific intervention. For centuries, medicine was organized around episodic, acute care; recently, advances in medical knowledge, lengthened lifespan, and changes in our environment have led to a new epidemic of chronic disease. Yet many stakeholders still favor the near-term: humans, both patients and clinicians, tend to devalue delayed rewards; payors and venture capitalists want fast return on investment; politicians want impact during their term. We may claim to value proactive, forward-looking care, but our actions - how we reimburse, invest, and measure performance - suggest we think good care is care with a short time to impact.

What would happen if we committed to a new definition of good care, one where proactive thinking and long-term outcomes were treated as foundational? First, we would need to rebalance investment toward prevention; right now, primary care and public health, both central to prevention, are underfunded compared with procedural specialties. Our public health infrastructure lags behind much of the developed world. Next we should fund and scale interventions that keep people healthy or reverse early disease. These tools are less often medications or medical interventions and more often lifestyle changes. Some well-studied tools exist, such as motivational interviewing, SMART goals, and brief action planning. These historically have been high-touch and time intensive for clinicians, with minimal reimbursement, but new technology promises the possibility of retaining the high-touch and personalized nature of these interventions with less time requirement for the clinician. Just as importantly, we would need to find ways to reward both patients and care teams for choosing lifestyle interventions; while pharma has incentive to market blood pressure medications, who gets rewarded for the more time-intensive process of education and supporting a patient who is trying to follow the DASH diet while on SNAP?

The longevity movement and the success of wearables have shown that there is consumer interest in more extensive biological monitoring; if we shifted the idea of good care towards more long-term goals, we would need more focus on how to make these data actionable in an evidence-based way.

Patient-defined outcomes vs. expert-defined outcomes

Today’s health system largely equates good care with expert-defined metrics: blood pressure control, Hemoglobin A1c control, colorectal cancer screenings, length of stay, readmission rates. While these measures have some overlap with the things patients care about, they are often several steps removed from what matters most to patients. In some cases, they may even conflict with a patient’s goals or beliefs.

However, patient-defined outcomes have historically been far harder to measure and track; they are inherently personal, endlessly variable in content and timeframe, ever-evolving, and resistant to neat, structured data fields. In addition, in more paternalistic eras most clinicians felt that patients should not or could not be trusted to know what mattered most. Thus, definitions of good care have long had a bias toward expert-defined, population goals rather than patient-defined, individualized goals.

What would happen if we changed our definition of good care to center more on patient goals? There have been some attempts to create this shift. The Larry A. Green Center has developed a Patient Centered Primary Measure to track whether a patient feels they have a strong relationship with their primary care team and whether their goals are being met. Patient confidence measures have been shown to correlate with outcomes, and gauge whether practices help patients gain the skills and agency to control their health. The Geriatric 5Ms help highlight priorities such as mobility, mentation, and “what matters most” that are often highly important to patients but at times overlooked in disease-specific metrics. Artificial intelligence may allow for unobtrusive ways to track whether patient goals are being identified, revisited, and met.

However, if we were to truly refocus good care on understanding and helping patients meet their goals, we need further change. We need payment models like direct primary care or APCM that reward deep discussion, goal-setting and frequent check-ins. We must address socioeconomic barriers that often are the true barriers to goals. Finally, we need better technological support to document goals, not just diagnoses; we need streamlined ways to identify, document and track evolving patient priorities and shared-decision making alongside condition lists and medication data.

Continuity vs. access

For much of the 20th century, continuity of care was a given. Your primary care physician would see you in the clinic and follow you in the hospital; seeing multiple specialists was uncommon; urgent care centers did not exist. But a number of factors have shifted the balance away from continuity and relationships and towards a focus on access at all costs: a shortage of primary care; the vast explosion of medical knowledge and subspecialization; the advent of hospitalists, clinician work-life balance expectations; urgent care and direct to consumer episodic telehealth services; consumer expectations. There are times that patients need access above all else, but continuity with the same physician has been shown to actually reduce mortality. What would we need to do to recenter our definition of good care around relationships and continuity?

First, we would need to measure continuity reliably. Few systems track whether patients consistently see the same clinicians or what percentage of their care is with their core team. Next, we would need to align relationship-based care. In the fee-for-service model, it makes little business sense to leave slots open for same-day or semi-urgent appointments for one’s own patients; if those slots go unused, that is revenue lost. Payment models must instead reward the availability and flexibility that enable continuity. Finally, we need team-based and technological solutions that maintain connection and provide access without fragmenting care. Dr. Ilana Yurkiewicz explores these themes of data and care discontinuity in her book Fragmented.

Thought experiments to make these ideas more tangible

Think through the following cases. What tradeoffs are at play? How would different stakeholders evaluate this care, and why?

Mr. Thomas is a 78 year old retired security guard with severe congestive heart failure (CHF). He is on oxygen around the clock and gets breathless speaking more than a few sentences. Three months ago he was intubated and successfully extubated during a CHF exacerbation, and while the experience was harrowing he feels these heroic efforts afforded him what he values most: time with his wife and children. This experience leads him to repeatedly tell his primary care doctor, who he trusts deeply, that he wants full resuscitation and only would choose comfort care if there is no hope of quality of life. During the last three months of his life, he is admitted to the ICU for bipap (a form of non-invasive ventilation) on 5 separate occasions. On the final admission, he requires intubation to support his breathing. His hospital team is unable to successfully extubate him after several weeks, and his family chooses to transition him to comfort care. He dies peacefully.

A local free clinic is able to support uninsured patients with diabetes with reduced cost medications using part of their donation income. Insulin in vial form is significantly cheaper than insulin pens. Although most people prefer the pens for their portability and ease of use, the clinic makes a policy that only patients who are unable to use vials due to physical limitations (poor dexterity, etc) qualify for free pens.

A patient goes to a clinic that offers screening full body MRI scans every 2 years. She pays out of pocket. After seeing her results, she is motivated to make some lifestyle changes when she sees that she already has visible plaque built up in her arteries. She is also found to have a 1.1cm thyroid nodule. She undergoes a biopsy, which is negative but results in a small hematoma and requires repeat monitoring by ultrasound. Her next scan shows a 6mm pulmonary nodule; she undergoes a repeat CT scan for follow up in 6 months (insurance will not pay for another MRI) and the nodule is gone.

Really great read. Thank you for your work in summarizing this. I've been talking to a number of colleagues about how the problems within healthcare are not necessarily complicated, but the incentive structure is what complicates the solutions. This piece did such a good job of illustrating that dynamic. The great solutions in healthcare seem to align incentives, more than just solve problems.

Excellent framework! Mapping stakeholder blind spots and tradeoffs is essential for aligning healthcare systems around truly patient-centered care